About Money: Lapham's Quarterly Highlights

Curating histories greatest minds as it relates to money

This essay will be the highlights and commentary of my favorite excerpts from the Spring 2008 issue of Lapham's Quarterly, About Money.

Lapham’s Quarterly is a quarterly periodical that contains quotes and essays from the greatest minds of history about a specific topic. This issue, About Money, includes excerpts from Hammurabi, Ben Franklin, Mozart, and more.

Let’s dive in.

The Value of Labor

1748 - To my Friend A. B.,

As you have desired it of me, I write the following Hints, which have been of Service to me, and may, if observed, be so to you. Remember that time is Money. He that can earn Ten Shillings a Day by his Labour, and goes abroad, or sits idle one half of that Day, tho' he spends but Sixpence during his Diversion or Idleness, ought not to reckon That the only Expense; he has really spent or rather thrown away Five Shillings besides.

Benjamin Franklin writing in “Advice to a Young Tradesman”, coining the phrase “time is money”.

This quote helps to understand Franklin. One of the world's last renaissance men, Franklin prided himself in his “industriousness” and efficient use of time. He basically invented “rise and grind”.

Franklin’s personality left a large imprint on the DNA of America. As our first international celebrity and the architect of some of our oldest institutions, there is an argument to be made that Franklin contributed to the stereotypical American work ethic that is prevalent today.

Balancing Accounts

1780 BC - If a merchant entrusts money to a broker for some investment, and the broker suffers a loss in the place to which he goes, he shall make good the capital to the merchant.

If anyone fail to meet a claim for debt, and sell himself, his wife, his son, and daughter for money or give them away to forced labor, they shall work for three years in the house of the man who bought them, or the proprietor, and in the fourth year they shall be set free.

Hammurabi, King of the Babylonian Empire, was most famous for his legal code which was the first to codify “an eye for an eye”.

The first law above focuses on investing. To clarify: “If an investor entrusts money to an entrepreneur, and the venture loses money, the entrepreneur is legally responsible for paying back the investor.” Modern investing does not work this way. If I invest in a company, and it fails, I am not legally obligated to get my money back. This is a pretty good deal for the investor… In fact, it’s so good that I can’t see why anyone would bother being an entrepreneur in ancient Babylon. Given this context, the law seems puzzling: why favor the investor so strongly?

It likely has to do with information asymmetry. “Entrepreneurs” for most of history were not what you would think of today - they were just guys with an idea. A venture could have been “hey, I heard about some cheap leather in a far away land. Want to fund my voyage and we’ll split the profit 50/50?” Without this law, an unscrupulous entrepreneur could easily fabricate a loss and defraud the investor. This would defer investors from ever investing in anything. Thus, Hammurabi's law aimed to foster investment and honesty in early economic ventures. The downside was that only extremely safe ventures were undertaken, because the entrepreneur would be on the hook for the money even if it was legitimately lost.

Which brings us to the second law, which shows what happens if the debt wasn’t repaid: debt bondage. Historically, most societies were creditor-oriented, favoring lenders. In contrast, modern societies typically protect debtors, a relatively recent shift. The worst thing that happens to defaulters in developed nations is bankruptcy, the punishment being it becomes hard to get another loan. This is painful, no doubt, but it’s a whole lot better than slavery.

Work is hard

1778 - This I am now doing in the fond hope that some change may soon occur; for I cannot deny, and indeed at once frankly confess, that I shall be delighted to be released from this place. Giving lessons is no joke here, and unless you wear yourself out by taking a number of pupils, not much money can be made. You must not think that this proceeds from laziness. No! It is only quite opposed to my genius and my habits. You know that I am, so to speak, plunged into music— that I am occupied with it the whole day— that I like to speculate, to study, and to reflect. Now my present mode of life effectually prevents this. I have, indeed, some hours at liberty, but those few hours are more necessary for rest than for work.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, writing when he was 22 about how he doesn’t like his job.

This passage is awfully humanizing for someone who seems so ethereal. To be honest I don’t have much to add here other than that child prodigies have to work too.

Free Silver!

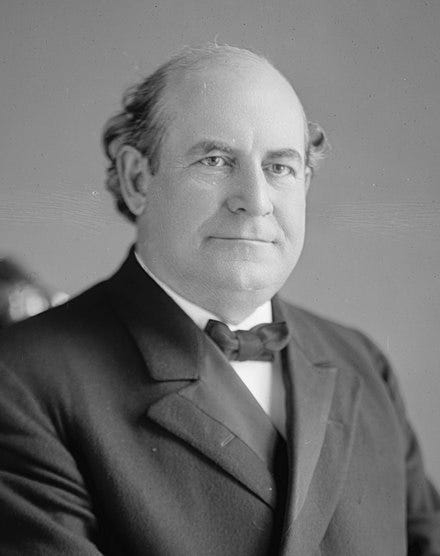

1896 - If they dare to come out in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we will fight them to the utter-most. Having behind us the producing masses of this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, the laboring interests, and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns; you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!

William Jennings Bryan, famously known as 'the Great Commoner,' was a three-time presidential candidate and a renowned orator.

Want to know one of the biggest political issues of the late 19th and early 20th century? Silver. The free silver movement, aimed to expand the money supply by backing it with silver in addition to gold.

In the late 1800s, the Silverites' advocacy for a bimetallic system stemmed from a unique economic challenge of their time: deflation. Yes, you heard that right. The issue of the day was not inflation, where prices go up, but deflation, where prices go down.

But isn’t deflation a good thing? Your $10 goes from buying one chicken at the beginning of the year to two chickens at the end of the year. Who wouldn’t want that? Debtors don’t. In a deflationary scenario, while $10 might buy more, it also means debts become heavier burdens, as the real value of money owed increases. Conversely, inflation can ease debt burdens, making the real value of what's owed decrease over time. When a monetary system is fixed to gold, inflation tends to be very low because the money supply cannot expand without additional gold reserves.

The majority of debtors at this time were farmers, who got their loans from bankers in New York. Ongoing deflation meant farmers' debts became greater in real terms, while the bankers profited from the increasing value of repayments. You probably can see where this is going… Advocates of the Free Silver Movement argued that introducing silver alongside gold as a currency standard would induce inflation. This inflation was seen as a means to alleviate the farmers' debt burdens and counterbalance the bankers' growing profits.

Despite Bryan’s talents as an orator, “you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!”, the Free Silver Movement ultimately failed. The biggest reason for the failure being the discovery of large gold deposits in Alaska and South Africa, which expanded the money supply and eased deflation.

Touring America

1832 - In nations where the aristocracy dominates society and keeps it immobile, the people eventually become accustomed to poverty as the rich do to opulence. The latter do not concern themselves with material well-being because they possess it without effort; the former do not think about it because they have no hope of acquiring it and do not know it well enough to desire it. In those kinds of society, the poor man's imagination is diverted toward the other world. Though gripped by the miseries of real life, it escapes their hold and seeks its satisfactions elsewhere. By contrast, when ranks lose their distinctions and privileges are destroyed, when patrimonies are divided and entitlement and liberty spread, the longing to acquire well-being enters the imagination of the poor man, and the fear of losing it enters that of the rich. A host of modest fortunes are amassed. Those who possess such fortunes enjoy sufficient material gratifications to conceive a taste for them and not enough to be content with them. Hence, they are forever seeking to pursue or hold onto pleasures that are as precious as they are incomplete and fleeting.

Alexis de Tocqueville was sent by the French government in 1831 to try to understand American society, which resulted in the seminal work Democracy in America.

The contrast that Tocqueville is making between Europe and America is ultimately one of class structures and upward mobility. America’s relative lack of a rigid class hierarchy is a key advantage it had versus Europe in the mid 19th century.

While there isn’t much direct evidence of influence, much of this quote aligns with how Hegel viewed historical progress (I wrote about some of his ideas here). Tocqueville's observations on American society's fluid class structure mirror Hegel's concepts of historical progress and the lord-bondsman dialectic. Additionally, Hegel believed that Christianity provided the lower classes with recognition, which Tocqueville echoes with the line “the poor man's imagination is diverted toward the other world.”

Quotes

Who is rich? He that is content. Who is that? Nobody. - Benjamin Franklin, 1755

Formula for success: rise early, work hard, strike oil. - J. Paul Getty, c.1950

October. This is one of the peculiarly dangerous months to speculate stocks in. The others are July, January, September, April, November, May, March, June, December, August, and February. - Mark Twain, 1894