Book Review: The End of History and the Last Man

A deep dive into Fukuyama's controversial idea

Starting in 1989, a revolutionary wave rippled across the world. This series of revolutions has been called the Autumn of Nations or the Revolutions of 1989, but is most popularly referred to as the Fall of Communism. Nearly every country in the Eastern bloc had a revolution that ousted their communist governments from power. For the 50 years prior to 1989, the world had been engaged in a war of ideologies, and one had just been crowned victorious.

Written by Francis Fukuyama in 1992, The End of History and the Last Man is about contextualizing the end of the Cold War into a framework that interprets human political and economic systems as a linear progression towards liberal democracy. But before we go more into what The End of History is about, we first need to discuss what it is not about.

The most common interpretation of The End of History, usually from those who have not read it, is that the fall of the USSR has led to a situation in which history is over, and that nothing interesting will ever occur again. I’m not strawmanning their opinion here, this is the way that Fukuyama is usually described. For example, here is Max Brooks on Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History Addendum podcast blaming Fukuyama for the current state of our institutions:

This notion that it is the end of history, beginning in the 1990s, that the great challenges of the human race are over, has 'f**ked us'.

This misinterpretation of the book's thesis has led Fukuyama to become the guy who was “more wrong than anyone has ever been before”. Anytime anything of note occurs in the world, people use it as a reason to dunk on him and the thesis that nothing would ever happen again (see here).

The End of History is ultimately about the philosophy of different political and economic systems. Humans have tried many different iterations of these systems, but we no longer need to keep searching. Liberal democracy is the last and final system of government that we will ever need. If Fukuyama wanted to be less provocative, he could have named his book: The End of the Need for Political Systems Other than Liberal Democracy.

Correct references to this book rightly determine that Fukuyama believes in the finality of liberal democracy. What I never hear though, is why. Why is liberal democracy the final form of human organization? What are the implications of that? Is Fukuyama even right about this? These are all questions that I will try to address.

I.

Liberal democracy can mean different things to different people, so I want to start with some definitions. First, we must break the phrase into its two components: “liberalism” and “democracy”.

By “liberalism”, I do not mean the ideology of the US political left. For the purposes of this essay, we will be using the strict definition of liberalism, which is the rule of law that recognizes individual rights and freedoms from government control. Or, if you prefer a more official definition: “A political theory founded on the natural goodness of humans and the autonomy of the individual and favoring civil and political liberties, government by law with the consent of the governed, and protection from arbitrary authority.” Liberalism is about the natural rights of individuals.

Democracy on the other hand is pretty straight forward. Derived from Greek as meaning “rule by the common people”, it is the practice of all citizens having a direct or indirect share of political power. Combine it with liberalism and you get the go-to societal system across the western world.

But do they always need to go together? Can a government be liberal without being democratic, or vice versa? While rare, there are some examples of each of these. 18th century Britain was relatively liberal, but not democratic, and Iran during part of the 20th century had a democracy without being particularly liberal.

There will undoubtedly be debate as to which countries are considered liberal or democratic, since most people have their own thoughts as to where that line is. Fukuyama gives some rough definitions, but in the end doesn’t spend much time on this, so neither will I. Overall, I don’t think it affects the thesis if countries are included or excluded at the fringes. If you believe that the US is neither liberal nor democratic, then you will by default disagree with the thesis of the book.

Liberalism also has an economic manifestation, which is the “recognition of the right of free economic activity and exchange based on private property and markets”. Or simply: capitalism.

Moving back to the thesis of the book: if liberal democracy is in fact the final form of human organization, then that implies history is directional. It starts somewhere, and ends with liberal democracy. This theory of directional history is in direct contrast to what the originators of political theory believed, which is that history was cyclical.

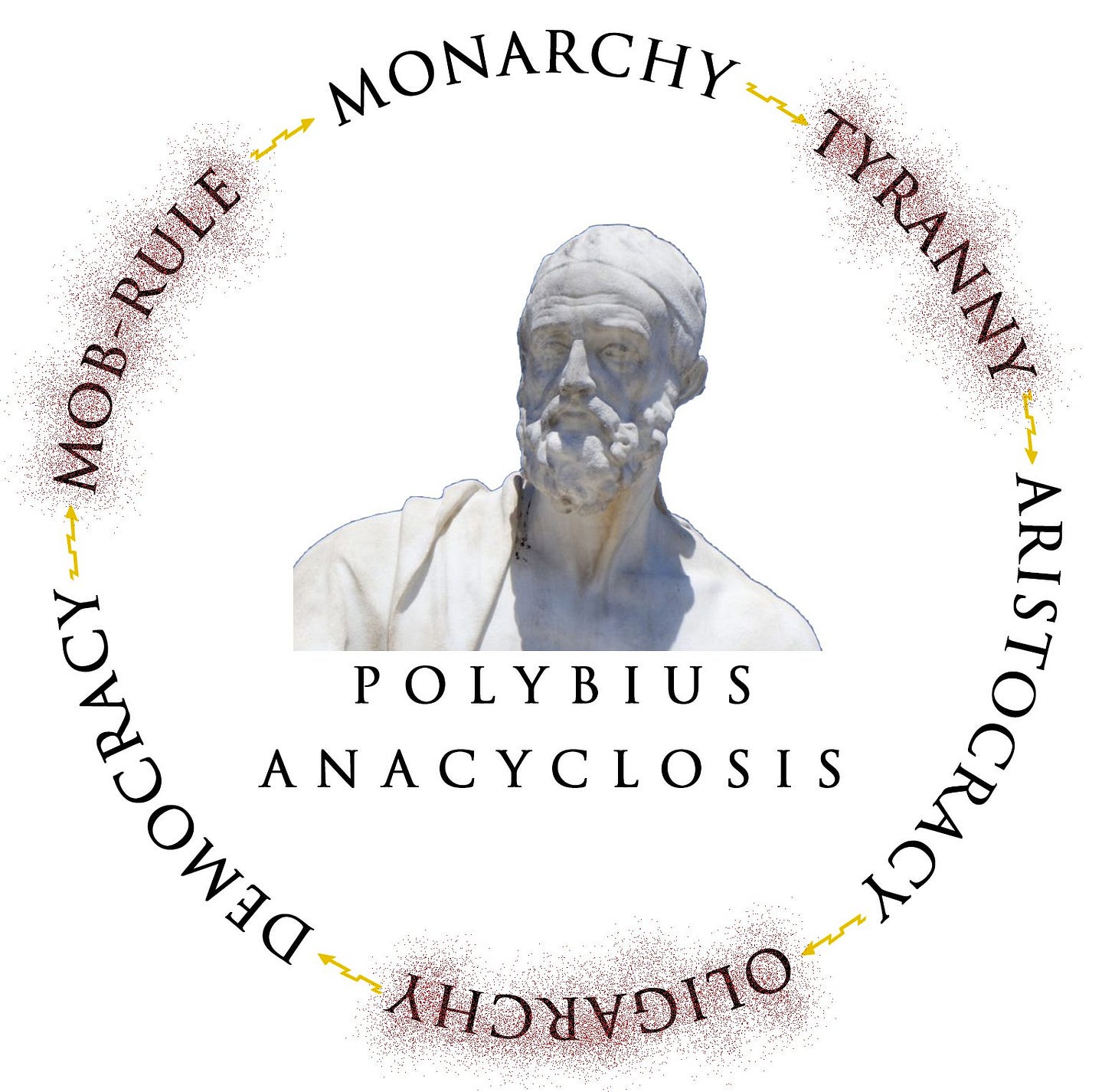

Plato and Aristotle both wrote about the cycles of government, but it was the ancient historian Polybius (200 BC - 118 BC) who most succinctly puts together the theory of kyklos (Greek for “cycle”). Kyklos goes like this, there are 3 systems of government that work towards the common interest: monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. But each of these has a degenerative form that works for the interest of the ruler(s): tyranny, oligarchy, and ochlocracy (mob rule/anarchy), respectively.

Society starts off as an ochlocracy, but is soon tamed by the strongest individual for the benefit of the whole (monarchy). Over time, the successors degrade in quality until you get tyranny. The leading citizens then dispose of the tyrant and set up an aristocracy, which, a few generations down the line, devolves into an oligarchy. “The people” then overthrow the oligarchs, forming a democracy, which eventually turns into an ochlocracy, starting the cycle over again.

According to the Greeks, the reason for this cycle was that humans could never be fully satisfied by any of the regimes, which would cause them to degenerate and transition to the next.

Kyklos remained the primary theory for political progress for nearly 2,000 years. In the 19th century however, philosophers began proposing a bunch of alternative theories that explain why history and human progress are linear rather than cyclical. One of the most important versions of these linear Universal Histories was written by the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831).

II.

Hegel is, without question, the main character of The End of History. Using the groundwork laid by Kant, he describes how humans progressed from our earliest organizational structures to our last. According to Hegel, history ended after the American and French Revolutions with their implementations of liberty and equality. Systems of political organization based on these principles were final because they did not have any internal “contradictions”.

Hegel’s claim was not profound because it described an end of history, but because he was able to explain why. Hegel fulfills the Kantian Universal History by describing the exogenous force that drives social institutions forward: recognition.

The greatest human desire, above all others, is to be recognized by others. In fact, this is precisely what makes us different from animals in the first place. This is why we place value on things with no intrinsic value, like medals or flags. Hegel’s “desire for recognition” was not and is not a new concept. Similar ideas have been pondered across the millennia: Plato spoke of thymos, Rousseau of amour-propre, and Hamilton of the love of fame.

Given that Plato was the first and only one to synthesize the idea into a single word, we will use the word thymos from now on. Generally, thymos is the human desire for recognition, but it can also be broken down into two different types: megalothymia (desire to be recognized as superior) and isothymia (desire to be recognized as equal).

In the beginning, what Hegel calls the “first man”, the megalothymatic drive led our political systems to be based on a master and slave relationship. This does not literally mean a master and slave relationship (though it can), but instead describes any structure that places one or a few individuals (masters) politically and morally above others (slaves). Monarchy, feudalism, and imperialism are examples of master-slave organizational structures. However, lurking beneath these systems are internal “contradictions” that make them inherently unstable, because both the master and the slave’s thymotic desires are unfulfilled.

The desire to resolve this contradiction, the slaves ongoing quest for recognition is what drives society forward to a state where all people are recognized equally.

Now this may come off as philosophical hand-wavy mumbo jumbo, which it sort of is, but the concept is relatively easy to grasp. While abhorrent today, autocratic social structures were accepted as “correct” for thousands of years, but their inability to provide proper recognition to their constituents led to their natural evolution to other structures that in-turn provide more recognition.

“More recognition” first comes to us in a big way with Christianity, which was the first major ideology to espouse universal freedom. Christianity gave slaves an outlet to satisfy their thymotic desire (isothymia), or recognition of being equal. Every human was now free. Not free in the Hobbessian physical sense, but in the moral sense of the equal ability to do right in the eyes of God. It did not matter if you were literally bound to a cage, as long as you were moral you would be judged and recognized fairly by God.

However, similar to Marx’s critique of Christianity (“opiate for the masses”), Fukuyama explains how it acted primarily as a thymotic outlet for slaves. It allowed the slaves to become more complacent with their current lack of recognition in return for the belief that they will be recognized when they reach the pearly gates. You may be satisfied in your cage, but you are still in a cage. (I will again note that I am not necessarily referring to chattel slavery, but instead the people in society without any power).

The way I interpret Fukuyama interpreting Kojeve interpreting Hegel here is that while Christianity had the right idea, it was really just a coping mechanism that acted in the masters favor to continue the pacification of the populace. Taken even further, the slaves just replaced their current master with a different one: God.

According to Hegel, the Christian did not realize that God did not create man, but rather that man had created God.

It wasn’t until the Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries that these Christian ideals of equality and freedom were not just heard from behind the pulpit, but in coffee-shop discussions about government. The modernized ideas were then implemented by two very important developments towards the end of the 18th century: the French and American Revolutions.

III.

According to Hegel, the French Revolution took the ideals of Christianity, that of equality and freedom, and brought them down to earth.

Rather, it constituted a recognition that it was man who had created the Christian God in the first place, and therefore man who could make God come down to earth and live in the parliament buildings, presidential palaces, and bureaucracies of the modern state.

However, the founders of the French and American Revolutions did not make this epistemic leap on their own. They stood on the shoulders of the enlightenment philosophers who converted the ideas of Christianity into an implementable and philosophically consistent moral framework.

Two such philosophers, John Locke and Thomas Hobbes, believed the value of liberalism was in the social contract between individuals to not interfere with each other’s natural rights. These rights would then allow people to satisfy their own desires. Said another way, the natural right of “the pursuit of happiness” is to not impede one’s ability to “pursue” happiness. The natural right is not happiness itself, but the right to pursue it - therefore according to Locke and Hobbes (along with the American founding fathers), unalienable natural rights were means to an end. That end being desires like wealth and happiness.

Hegel, on the other hand, saw rights as ends in themselves. His controversial insight is that what humans desire most is not material prosperity, but thymos: recognition of their dignity. Liberal democracy encapsulates this because everyone is universally recognized by the law. Being recognized as having the right to pursue happiness is more important than happiness itself.

This is ultimately why Hegel believes that liberal democracy is the end of history. There are no longer any “contradictions” of recognition for any actor within the system. All individuals in a liberal democracy are recognized as important, reflected in the protection of their natural rights and the right to democratically express opinions.

Of course, one would say that our liberal democracy does not necessarily “recognize everyone universally”, with two looming examples being African Americans prior to the 15th Amendment or women prior to the 19th. Although, these act as the exceptions that prove the rule. The very fact that there is a 15th and 19th amendment shows liberal democracies impressive ability to resolve its own contradictions as they arise, something that monarchies are structurally incapable of doing.

But what of megalothymia? Doesn’t some people's innate desire to be recognized as better than others represent a contradiction for liberal democracy? This is our most dangerous trait, many of history's great disruptors were driven by it, such as Caesar, Napoleon, and Stalin. These individuals are dangerous because if their megalothymia goes unchecked, it can quite literally bring down society. While Fukuyama believes this is the greatest threat to liberal democracy, it does not represent a true contradiction because of the mechanisms we have that “absorb” it.

First, the American Founders were very intentional about taming megalothymia when they wrote the Constitution. They may not have had Napoleon or Stalin to learn from, but they certainly knew about Caesar. For example, the separation of powers was designed to prevent tyranny, which is caused by megalothymatic behavior. Queue Montesquieu:

When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty; because apprehensions may arise, lest the same monarch or senate should enact tyrannical laws, to execute them in a tyrannical manner.

With these checks in place, political elections are then a perfect outlet for megalothymia. Those with ambitions of superiority can go through the pure competition of elections, and eventually reach the top. Their megalothymia will be satisfied, but the “top” position is incapable of societal destruction.

Perhaps the greatest outlet for megalothymia in liberal democracies is entrepreneurship and other economic activity. Work is necessary so we can satisfy our basic needs like food, clothes, and shelter. But beyond that, economic work quickly leads to an outlet for thymos. This is most obviously seen when looking at the extreme end of the wealth spectrum. Would the robber barons have tried to take over the country if they didn’t have entrepreneurship to quell their megalothymatic drive?

While politics and entrepreneurship may be the strongest outlets for megalothymia, there is none purer than sports. Sports have no point other than to determine if one group is better than another group. Without war, the classic traditional struggle, we have resorted to other ways of winning recognition by creating fake conflicts with sports.

Just as liberal democracy changes the dynamics of the individuals, it also affects how the nation state interacts with other nation states. First, is the incompatibility of imperialism with liberal democracy. There is a reason why the decline of imperialism tracks inversely with the rise of liberal democracy (there is a delay, but it's noteworthy). Imperialism is just the master-slave relationship at the highest level and represents the masters of one nation enslaving the masters of another. Going to war for erroneous reasons is another example of this. People used to be sent to war for the glory of the leader, which would occur at the drop of a hat, whereas today war is a much tougher sell.

The leaders of liberal democracies must convince their populations to go to war, instead of disregarding their opinions all together. Included in this convincing, they need to construct narratives that will be effective in getting the citizenry to subscribe to a specific war. These narratives coincidentally tend to target enemies that have a different system than liberal democracies. In other words, liberal democracies almost never target each other. This is perhaps the most important point when it comes to the question of “what are the implications of a world full of liberal democracies”. In the 200+ years with liberal democracies, we have very few instances of one going to war with another.

IV.

I now want to go through some common objections to The End of History. But first, let's recap:

Hegel believed that the ultimate force driving the plot of our Universal History is the human desire for recognition, or thymos. Any system of government that fails to provide thymos to all its people has contradictions that make it inherently unstable, and will eventually evolve to a system that provides more thymos. Introduced after the French and American Revolutions, and built on the ideals of the enlightenment, liberal democracy is a system free of any thymotic contradictions. Since it has no internal contradictions, and can adapt itself to resolve contradictions that do arise, there are no further systems that can replace it. This means that over time, we will trend to have more and more liberal democracies, until all that is really left is liberal democracies, hence the end of history. While this does not mean nothing will ever happen again, it will mean less war and more human rights, which is objectively good.

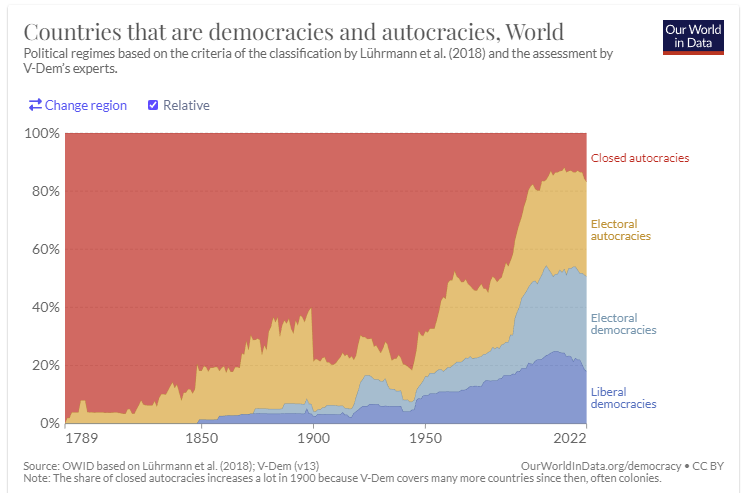

Objection 1: “Democracies are actually on the decline, which invalidates the thesis.”

That’s nice, but is it true?

This objection is 100% true… when evaluated at a time frame of 20 years. When viewing it at a century level scale it tells a much different story. I am going to assume that Fukuyama would argue that the above graph is the proper length with which we should view the trend.

While it’s certainly not a smooth linear increase, the trend is very much up and to the right for democracies. I don’t think the thesis is invalidated by the downtrend of the last 20 years. Fukuyama’s opinion in 1992 isn’t much different than it is today. Sure, a lot of people don’t live in liberal democracies, and there are some successful countries that don’t have liberal democracies. Despite this, there isn’t a danger of the systems themselves overtaking the mindshare that liberal democracies currently have. China focuses a lot on exporting its goods and its political influence, but it doesn’t really outsource its ideology. There is no good alternative system that appears to be able to compete with liberal democracy.

Communism and to a lesser degree fascism, represented viable alternatives to liberal democracy in the 20th century, but both ended up failing. Why was that? Fascism's emphasis on militarism and war ultimately led to its demise. Even if the wars had gone in favor of Hitler and Mussolini, lasting peace would have led to a contradiction. Said another way, fascism only really works through war and conquest, and this either destroys the fascist nation if they lose, or removes the raison d'etre if they win.

Communism on the other hand had a few contradictions, but the main one was economic. Communism was even more dependent on economic success because its core mantra was to improve the standard of living for the average citizen. Remember that prior to the 70s, communism was considered to be better at driving economic growth than capitalism. Which is true in theory… just not in practice. In the end though, communism (or at least the variants that were tried) failed to increase the standard of living of the people.

Objection 2: “But what about Russia and China?!”

This is the most common objection to The End of History thesis. However, as I said in the previous objection - while China and Russia represent clear, and even successful aberrations from liberal democracy, they don’t actually propose viable alternatives. Given they are both autocracies, we already understand the contradictions that they suffer, and we have thousands of years of examples to know they will also suffer from the succession or “bad monarch” problem. The bad monarch problem stipulates that while monarchies can be the “best” form of government with a good monarch, you will eventually end up in a situation where you have a bad monarch, and the state will fail. (Coincidentally, this aligns with kyklos.) For more on this, see my essay on monarchical succession.

Objection 3: “What about the Scandinavian socialist countries? They seem to have a system that represents a viable alternative to liberal democracy.”

This objection is not really objectionable because all of these countries are liberal democracies. The degree of redistribution of wealth that a country decides to have, given that it was democratically determined, does not disqualify them from being liberal democracies.

Socialism has a very broad definition, and encompasses a lot of different systems, but the Scandinavian countries do not invalidate Fukuyama’s thesis. If these countries had command economies (like Venezuela), that would be different, but they are capitalist liberal societies that use democracy to determine a degree of redistribution that they are comfortable with.

Objection 4: “There are so many examples of failed democracies, if it really is the best form of government, why does it consistently fail?”

We’re looking at you, South America. This is honestly a good question, and Fukuyama spends quite some time in the book going over why sometimes countries fail to implement liberal democracies. The ultimate reason is of course thymos, but towards structures other than democracy. If a group of people have strong social norms that provide them thymos through other means, it can stymie the democratic process. Below are the cultural factors that can affect the prospects for stable democracy:

National, ethnic, and racial consciousness

Religion

Unequal social structures or classes

Of course, these are just obstacles, they are not immovable barriers. Many countries have been able to establish successful democracies despite having obstacles in these areas. The most extreme example is India, which has some of the world's worst religious differences and a nasty caste system. The fact that they have a relatively successful democracy is quite amazing.

Objection 5: “But what about the political decay occurring in the US? The success of democracy is not a foregone conclusion.”

I think Fukuyama of the 90’s would have been dismissive of this point, but his opinion seems to have evolved. Here is a recent quote from him: “twenty-five years ago, I didn't have a sense or a theory about how democracies can go backward. And I think they clearly can."

While I am sure this subject is covered in detail in one of his newer books, I have not read them so I can’t relay in detail what he would say. Although my opinion on the matter is that just like the three cultural factors in Objection 3 can stymie a democracy from forming, I think they can also cripple a historically strong democracy. Cultural factors are always changing, especially national consciousness and social structures. Despite this, I think established democracies are generally more robust than people think, and I don’t think this is a true objection to the thesis until a historically “strong” democracy actually unravels.

Objection 6: “Sure, democracies are growing over time, and all countries may eventually become liberal democracies. However, the reason is due to post-industrial revolution economic efficiency rather than ‘thymos’.”

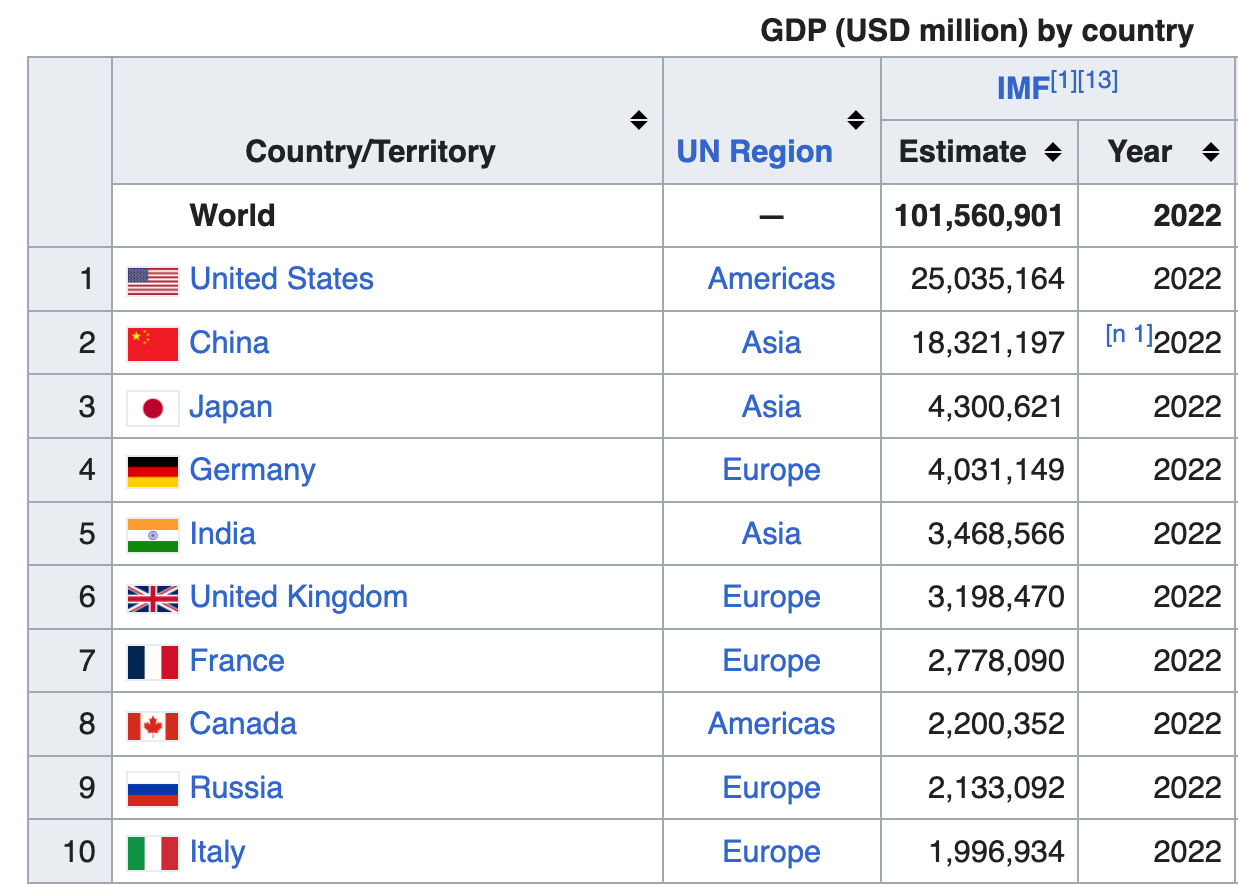

This objection relies on the assumption that democracies foster greater economic efficiency than other systems of government. Considering that 8 of the top 10 largest economies are democracies, it's not surprising that one would assume democracies best foster economic growth.

In order to address this objection, we first need to look at how developed countries became developed in the first place. Most of those in the above chart are developed, but of course at one time they were developing.

When looking at developing countries, it is not clear that democracy is better for economic growth, if anything it may act as a dampener. Most of the above countries had their strongest periods of economic growth under systems of government that were significantly less democratic than they are today. Examples include: Japan during the Meiji Restoration and during WWII occupation, Imperial Germany under Bismarck, the UK in the 17th and 18th century, and Russia and China have basically never been democracies. In fact, the only countries in that list that fully developed their economies as democracies are the US and Canada.

Here is a quote from Fukuyama, quoting Lee Kuan Yew, the “founding father” and prime minister of Singapore for 31 years.

The argument can and has been made most notably by former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore that a form of paternalistic authoritarianism is more in keeping with Asia's Confucian traditions, and, most importantly, that it is more compatible with consistently high rates of economic growth than liberal democracy. Democracy is a drag on growth, Lee has argued, because it interferes with rational economic planning and promotes a kind of egalitarian self-indulgence in which a myriad of private interests assert themselves at the expense of the community as a whole.

This hits on the reason why democracies are bad for developing economies. When societies are highly unequal, as those that are undeveloped tend to be, you need an authoritarian to bulldoze their way through entrenched special interests and structural inequality. Once these barriers have been removed you get to a spot where the economy can grow effectively and industrialize. The US and Canada didn’t have these barriers during their industrializations, because they were such new societies.

As industrialization leads to a more wealthy and educated populace, it increases the demand for recognition that does not exist with poorer and less educated people.This naturally leads to the transformation of the authoritarian society into a democracy. That is why 80% of the largest economies today are democracies, not because they grow the economy quicker.

Objection 7: “While communism may or may not be the answer, the structural economic inequality arising from capitalist systems implies, by default, unequal recognition. Also, how can you say we have universal recognition when X, Y, and Z groups are systemically marginalized?”

This objection would come from the political left, focusing first on economic inequality, and second on social/political inequality. Let’s start with the latter.

Fukuyama addresses this by first breaking inequality into two categories: conventional and natural. Conventional would include legal barriers to equality, such as voting rights, Jim Crow laws, Apartheid, etc. Natural inequality would be the unequal distribution of natural abilities or attributes. While this includes niche things, like we can’t all be NBA players, it’s primarily focused on intelligence. Or as Madison said, “equal facilities for acquiring property”.

A true liberal society should theoretically be dedicated to the reduction, if not elimination of conventional inequality. As the conventions change (women’s rights movements for example), the legal inequalities also change (19th Amendment). For a more recent example, as the Overton window shifted on gay rights, we began getting legal changes. The idea being that as a light shines on conventional areas of inequality, liberal democracies should adjust to accommodate (albeit slower than some people would like).

Economic inequality is more complicated. Fukuyama starts with how modern capitalist societies are much less unequal than the systems we had before. Which is true, but doesn’t necessarily prove there isn’t something more equal. We also have the ability to adjust how much we want to modify their current system to address existing economic inequalities. This would be the difference between a Scandinavian country with high tax rates and more social spending, than the US or Switzerland with less. However this does not disqualify “liberal democracy status”, see Objection 3.

Although, even if we were able to eliminate every source of conventional iequality, that still leaves the natural inequality inherent to capitalist systems. This is where Fukuyama separates liberal democracy, the political system, from liberal economic systems. To be honest, he leaves it very open ended, but I think the correct response to the economic part of this objection is that capitalism does not necessarily need to accompany liberal democracy into the future. It’s not clear exactly what would replace it, but in theory something could replace capitalism while leaving liberal democracy intact. I could be off-base here, but that is how I interpreted the way he ended the chapter:

The fact that nature distributes capabilities unequally is not particularly just. Just because the present generation accepts this kind of inequality as either natural or necessary does not mean that it will be accepted as such in the future.

Objection 8: “The issue with universal recognition is not its current inadequacy, but that equal recognition is the end goal in the first place.”

This would be the objection from the political right, best personified by one of Hegel’s biggest critics: Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900).

Nietzsche hoped for a new moral framework (or a reversion to an old one) that would favor the strong over the weak. He thought that megalothymia was not something that should be “tamed”, but instead something to desire. Universal recognition would dilute the quality of the recognition: what is the value of the recognition if you get it for just existing?

Nietzsche agreed with Hegel that Christianity was a slave ideology and that liberalism represented a secularized form of Christianity. But therein lies his concern - by removing the desires of the master, society loses out on what is noble and beautiful.

If this ideology seems a little radical and relatively hard to grasp, that's because it is. Modern society has stepped far away from what Nietzsche wanted, and only card-carrying reactionaries would agree we need to move back to monarchies.

But let’s steel man Nietzsche for a second. This objection ultimately rests on the idea that universal recognition will remove the creativity, beauty, and greatness out of our souls. For one thing, he’s right. Democracies do not produce nearly as many beautiful things as monarchies do. We don’t care about crown jewels and Fabergé eggs anymore, and modern architecture is a train wreck:

The most impressive building I have ever seen is the 1,500 year old Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Even the most iconic structures in the US capital copied 2,000 year-old designs.

This is obviously going to happen though. Democracies are just more practical than other forms of government. The US Department of Energy building is an office building, the Taj Mahal is a mausoleum for the emperor's favorite wife. It also doesn’t matter what the economic system of the democracy is either. Capitalism doesn’t find any ROI in extravagance, and socialism finds extravagance as antithetical to the goals of equity and equality. Democracies do create fewer beautiful than aristocratic or autocratic societies. Although, what they do exceptionally well is produce a lot of ugly things that are very, very useful.

Beyond this, we learned in the previous section that democracies don’t eliminate megalothymia. Physicists will still compete to find the theory of everything, directors will still try to make the best movie, and business people will still try to make the most money. These things are important, and I don’t think realizing universal recognition takes that away.

V.

So, was Fukuyama right? I think it's too soon to tell. If the 50-100 year trend of democracies begins to break, or we see established democracies begin to fall, then we can probably say Fukuyama was wrong.

But for now, liberal democracy remains the only viable ideology in contention, though this doesn’t necessarily mean it will always be. Or, to call on Hegel one last time: “I have the courage to be mistaken.”

[Thank you to Liam Knight for edits]