Successful Succession

Contrasting the English and Ottoman approaches to succession

No, this essay is not about the final season of Succession, but it is about succession. What if I asked you, “How would you design the best system for choosing a leader?” A key consideration you may have is how to get the most effective leader in charge, because obviously having a competent leader is objectively good. You may also consider the peaceful transfer of power. If your system doesn’t have an adequate way of switching leaders, your competent leader may end up fighting with others vying for the position, causing chaos for constituents. With these considerations, your response would probably include something about having elections every X number of years based on meritocratic principles with potential term limits.

However, what if I modified the initial question to include two constraints:

Constraint #1: the new leader must be blood-related to the existing leader

Constraint #2: the new leader must be male

These are the two constraints that most societies in history were working with when choosing their own succession methods. Let’s look at two examples.

England

It's worth noting that the succession methods of England changed throughout its 1,000+ year history. However, one constant was Christianity. This affected their succession process by restricting Constraint #1 to also require legitimacy. Not only did the new heir have to be blood related to the king, but they also had to be born of a church sanctioned marriage. Therefore, if the king had a child out of wedlock (ie. a “bastard”), they were out of contention for the throne.

With these constraints in place, the natural next question is which legitimate male child gets the throne? And what if there aren’t any male children?

The English used a system called male-preference primogeniture, which helps to answer the above questions. In regard to prioritization, we all know that the eldest male child gets the throne.

As for the latter question, the implications of the king having no male direct descendants differed throughout the years, but almost always led to a contested succession. During the early years of the English monarchy, the throne would pass to the king's closest male relative. This often meant that a younger brother, nephew, or cousin of the king would inherit the throne. However, there were many times in English history where no legitimate son led to the proximity of blood, which prioritized directly-related females (daughters) over male relatives more distant in the family line. This is why Victoria, and even Elizabeth II, became queen instead of the king’s brothers or nephews. A variation of these two systems was used for more than 1,000 years until 2013, when they dropped most of the constraints, making it an absolute primogeniture (eldest child of any gender, legitimate or not).

The value of primogeniture is that there is less debate around succession. Given that succession is one of the most common reasons for war and political upheaval over millennia, having a clear definition of who is next in line is highly valuable. Despite this, the transfer of power was not always smooth in England. The eldest male son was usually not disputed, but when there was no legitimate male son and the rules weren’t clearly defined, things got a little hazy.

A great example of this is shown through perhaps the most famous English monarch: Henry VIII, who notoriously struggled to conceive a male heir.

After countless failed attempts at producing a male heir with his first wife, Henry infamously broke from the Catholic Church to marry his mistress, Anne Boleyn. This resulted in a completely divided nation of Catholic vs. Protestant, all in hopes of bearing a legitimate male son. When Anne and Henry could not produce a male heir either, Henry beheaded Anne for “treason.” However, it's widely accepted that she was beheaded because Henry wanted another go at having a male heir with a different woman, Jane Seymour.

Jane Seymour was successful in providing Henry with an heir, giving birth to Edward VI in 1537. When Henry died in 1547, Edward went on to become king at the ripe age of 9 years old. While this transfer of power was smooth, I would argue that a 9-year-old cannot be a “competent” leader. Edward was a sickly teenager and ultimately died at age 15 with no male heirs of his own. Rather, he had two childless older sisters, Mary I and Elizabeth I, whom he decided to exclude from the line of succession before his death. Alternatively, he decided that his cousin, Jane Grey, would become queen so that her male heirs could succeed the throne.

As expected at the time, these actions led to conflict and bloodshed. Jane Grey was only queen for 9 days before she was overthrown by the more popular Mary I. During her contested reign, Mary was unable to conceive children, and upon her death the throne was succeeded by her half-sister, Elizabeth I. When Elizabeth also died with no children, the throne was given to the King of Scotland, and we were back to our direct descendent males-only club for the foreseeable future.

To bring us back to the point, the constraints of legitimate and male led to what can only be described as complicated. Additionally, Henry VIII had several illegitimate children throughout his life, including two known illegitimate sons. In a different part of the world, either illegitimate son may have had a direct claim to the throne and could have ended the need for beheadings, bloodshed, and religious turmoil. This leads us to a society with different rules: the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman empire was founded in 1299 and acted as the major power in Eastern Europe and the Middle East for more than 600 years. They were ruled by sultans, who had a very different succession practice than England. First, the Ottoman Empire was Islamic, which did not place the requirement of marriage onto the sultans. This meant the Ottomans were not bound to legitimate heirs.

Instead of wives, the sultans had a system of concubinage, which was a well-established practice in the Islamic world. Concubines were women in a dedicated relationship to the sultan, without legally being the sultan’s wife. A sultan could have tens to hundreds of concubines, who resided in the imperial harem.

You may see where this is going… The sultan had many heirs. For example, Sultan Murad III allegedly had more than 100 children.

Putting aside any moral judgements you may have; this system has obvious differences to the English system. First, the sultans and their many kids would never run into the male-less issue that Henry VIII faced. Second, the Ottomans did not have a formalized process for assigning one of the many male children as the successor to the throne. What they did instead was something called “open succession”.

Open succession could also be thought of as “survival of the fittest”, and was the primary method for assigning a male heir in the Ottoman Empire from 1300 until the early 1600s. During his reign, the sultan would appoint all his sons to various administrative roles across the empire, giving them all experience working in government. When the sultan died, his sons would then fight amongst themselves until a victor had been declared. As you can imagine, this process was very bloody. To make matters bloodier, once a son was crowned sultan, he would commit fratricide and kill all his brothers (many of whom were babies).

Now, most of the time the sultan did not leave the empire to a complete free-for-all after his passing. Through a handful of tactics, he could ensure that his favorite and most competent of his sons received positions that gave them a leg up during the impending melee. Any sons appointed to roles located at the palace in Constantinople (modern day Istanbul) would have a huge advantage over sons positioned hundreds of miles away. Time was everything after the passing of a sultan, and being close to the heart of the empire was a decisive advantage.

Not surprisingly, the Ottoman word for “successor” shares the same Arabic root as the word for “conflict”. All but one of the successions during the 200 year period during the 15th and 16th centuries were resolved through combat.

This system lasted until Sultan Ahmed I (1603-1617) decided to end the practice of fratricide to reduce the violence associated with succession. In its place, he introduced the Kafes system based on agnatic seniority. Agnatic seniority is just a complicated way of saying that the prioritization is brothers ahead of sons, oldest to youngest. However, doesn’t this still mean we have dozens of brothers, and to a lesser degree sons, that may want to kill the sultan and take the throne? Yes, it does. The Kafes system addressed this by keeping all potential successors in a middle-age version of house arrest until the sultan died (kafes literally means “cage”). The new sultan would then come out of house arrest and begin leading the empire.

(I think this is why it is relatively uncommon to see brothers of the monarch at the top of the succession line. They tend to want to kill each other anyway, so adding control of the kingdom to the mix tends to make this even worse.)

While the Kafes system did eliminate fratricide and the bloody succession wars, it also meant the Ottomans no longer received the most “competent” leader as sultan. Many of the new sultans during the Kafes system had no experience with anything and had been locked in the palace for most of their lives.

The system of agnatic seniority also increased the average age of the sultan and decreased the average reign. The average reign prior to Mustafa I (1617) was ~22 years (median 24 years), and after Mustafa it was 12 years (median also 12 years) (link).

Competence vs. Smooth Transition

The English and the Ottomans had very different systems of succession, but what are we solving for here exactly? If you recall the question I asked at the beginning of the essay, the two considerations raised for designing a system of succession were competence and smooth transfer of power. The importance of competence should be self-explanatory, but smooth transfer of power may require a little explanation. Transfer of power that was not smooth led to a ton of problems. Aside from the obvious bloodshed and societal degradation of a civil war, the rule of law itself would break down during times of uncertainty. Remember that laws as trivial as “is this small town allowed to have a market?” could be dictated by the current monarch. If the transition of power was contested, there was huge uncertainty around basic decisions governing everyday life until someone took the throne.

The competence of the leader and smooth transition of power represent a trade-off. Of course, this trade-off doesn’t exist today because we have a democracy, and hence are not bound to the bloodline of our leader (Constraint #1).

With this in mind, let’s look at how the English and the Ottomans differed in this area. Evaluating the English succession system, one glaring issue arises: prioritizing the eldest-male child had nothing to do with their competence as a leader. Their older sister or younger brother could be 10x the leader but have a tiny chance to become king or queen. Why didn’t they just choose the best or most competent child of the king instead? Well, because that would be subjective. Primogeniture (eldest son first) gives an objective determination of who the next leader is, which is key for resolving disputes and ensuring a smooth transition of power. We can see from the English system that they felt that a smooth transition of power was more important than the competence of the leader.

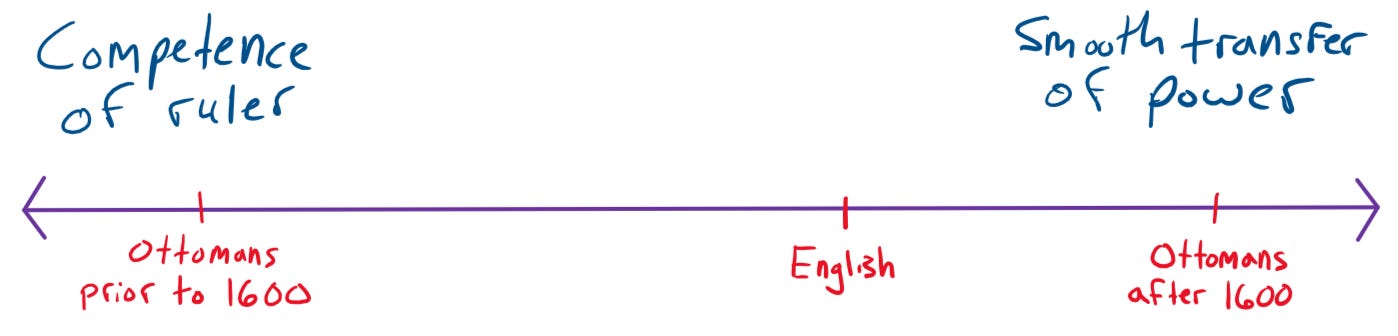

The Ottomans, prior to 1600, were the exact opposite. They went all-in on the competence of their leader through the “open succession” method, but that led to a virtual impossibility of having a smooth transfer of power. It’s interesting then that the Ottomans eventually switched their system to one of agnatic seniority instead of the merit-based system of open succession. This shows that they may have also felt a smooth transition of power was more important than a leader’s competence. Let’s graph this out.

I don’t think there is any argument in this ordering when it comes to the smoothness of the transfer of power. The data proves it out strongly. The Ottomans did not have a significant war of succession after 1600, whereas before they happened almost every time. The English on the other hand, had succession issues semi-often over their entire history. As for competence, I see any instance of a succession war as leading to a more competent leader, hence the trade-off. However, I’ll note that it's difficult to actually prove “competence” by any quantitative measure.

Another interesting difference between the English and Ottoman systems are their pool of potential heirs. The English restricted the stock of potential heirs through the constraint of marriage, whereas the Ottomans had no constraints with dozens of heirs.

After 1600, the English and the Ottomans were both using a hereditary prioritization system to the order of succession but had massively different stocks of heirs. What differences did this lead to? The obvious benefit of the Ottomans having dozens and dozens of brothers and sons is that there was never a question of who was next in line, which is why the post-1600 Ottomans are further right than the English on the above scale.

But remember that this is a trade-off: if the post-1600 Ottomans had a smoother transfer of power than the English (due to larger stock), that also means they had lower competence. Why would that be? For the reasons described before, the new sultans were now much older, and had no life experience due to being locked away their entire upbringing. The English, with their lower pool of heirs, had the occasional “no-son” issue, which reduced their smooth transfer of power. However, this would have led to more competent leaders since the more effective leader would ultimately win the succession battle. (See Elizabeth I, one of England’s most beloved leaders).

Concluding Thoughts

In conclusion, the succession systems of the English monarchy and the Ottoman Empire offer contrasting perspectives on how societies have historically grappled with the challenges of succession. The English system, with its constraint of legitimacy and a preference for primogeniture, prioritized a smooth transfer of power (in theory), even at the expense of the competence of the leader. The Ottomans, on the other hand, initially embraced a system that sought to select the most competent leader, but eventually shifted towards a system that favored a more peaceful transfer of power.

Both systems teach us valuable lessons about the trade-offs between the competence of the leader and the smoothness of the transfer of power. Today, democracy has largely replaced the constraints of hereditary succession, allowing for a more merit-based selection of leaders. But we must not forget the lessons of history as we continue to shape our political systems to ensure both competent leadership and peaceful transitions of power. By examining these historic succession systems, we can better understand and appreciate the progress we have made and the challenges that still lie ahead in the pursuit of the ever out of reach goal of effective governance.

Thank you to my editor (ie. girlfriend) Laurier for helping out with this essay.

Great work on this one. Never realized that drastic shift post-1600 in the Ottoman Empire.

Great read! There are definitely similar (less bloody) themes in American government today. While there may be a relatively smooth transition of power, are we truly electing leaders based on competence? Or is there a better way?