Book Review: Gödel, Escher, Bach

Everyone's favorite book they've never read.

They say that if you want to earn respect in prison, you should go up to the biggest guy in the yard and punch him in the face. While I cannot attest to the efficacy of such advice, the intellectual equivalent is writing a book review of Gödel, Escher, Bach.

Most people would describe the book to be about the intersection of math, art, and music (it’s not). Douglas Hofstadter became so frustrated about this misconception that he published a new book 30 years later titled I Am a Strange Loop, which presented a more succinct and less abstract version of what he was trying to say in GEB.

This review is mostly structured around I Am a Strange Loop, which conveniently also serves as a review of the major themes of GEB. Consider this a low stakes bait-and-switch, for which I hope you'll forgive me.

I.

Let’s talk about the levels of reality.

If someone asked, “what caused Hurricane Katrina?”, a normal answer would be about warm ocean water evaporating, or something. This is a high-level explanation that is useful in explaining the cause of a hurricane. You could go a level deeper and say hurricanes are caused by a bunch of water molecules interacting with each other. This is also correct, it’s just not very useful - whenever anything occurs, it's ultimately due to atoms interacting with other atoms interacting with other atoms. You could then go one level deeper and begin describing the specific water molecules involved in Hurricane Katrina. Of course this would be insane, there are 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 H2O molecules in a cup of water. To describe how each one contributed to the hurricane would take more time than the age of the universe. Despite the lowest level of reality - atoms interacting with each other - being responsible for everything, we do not and cannot use this level for explanation or understanding. Instead, we are forced to abstract to a higher level.

Above atoms (physics) is the world of molecules and chemical reactions (chemistry), and above that is the world of cells (biology). But even the biological level is insufficient to understand the function of complex systems. Take the heart, for example. Analyzing billions of individual heart cells does not help us understand what a heart does. Instead, we need to transcend the biological and venture into the realm of philosophy, where we seek to understand purpose. The purpose of a heart is to pump blood. The concept of a “pump” is not visible at the atomic level, nor the molecular level, not even at the biological level. But in one word, “pump”, I can describe to you the interaction of septillions of atoms and billions of cells. Not only is this the best way to explain a heart, but it’s also the only way. Our entire existence is just molecular physical processes that we abstract to higher levels to understand.

This abstraction can be seen outside of nature too. Take this example from GEB:

Anteater: Perhaps I can make it a little clearer by an analogy. Imagine you have before you a Charles Dickens novel.

Achilles: The Pickwick Papers - will that do?

Anteater: Excellently! And now imagine trying the following game: you must find a way of mapping letters onto ideas, so that the entire Pickwick Papers makes sense when you read it letter by letter.

Achilles: Hmm... You mean that every time I hit a word such as "the" I have to think of three definite concepts, one after another, with no room for variation?

Anteater: Exactly. They are the 't'-concept, the 'h'-concept, and the 'e'-concept, and every time, those concepts are as they were the preceding time.

Achilles: Well, it sounds like that would turn the experience of "reading" The Pickwick Papers into an indescribably boring nightmare. It would be an exercise in meaninglessness, no matter what concept I associated with each letter.

Anteater: Exactly. There is no natural mapping from the individual letters into the real world. The natural mapping occurs on a higher level-between words, and parts of the real world. If you wanted to describe the book, therefore, you would make no mention of the letter level.

Achilles: Of course not! I'd describe the plot and the characters, and so forth.

Anteater: So there you are. You would omit all mention of the building blocks, even though the book exists thanks to them. They are the medium, but not the message.

Additionally, the lowest level physical processes are completely irrelevant to whatever goal that we are trying to achieve. If a mechanical engineer is building a car engine, it does not matter what the trajectory and velocity of each molecule will be. What matters is that, with certainty, the piston will be pushed out when heated to the correct temperature and combustion occurs.

Abstraction is a process by which complexity is made comprehensible, giving us the ability to understand.

II.

Let’s now look at another example of abstraction: the mind. In the same way we can’t understand a hurricane by looking at water molecules, Hofstadter claims we cannot truly understand consciousness by looking at neurons.

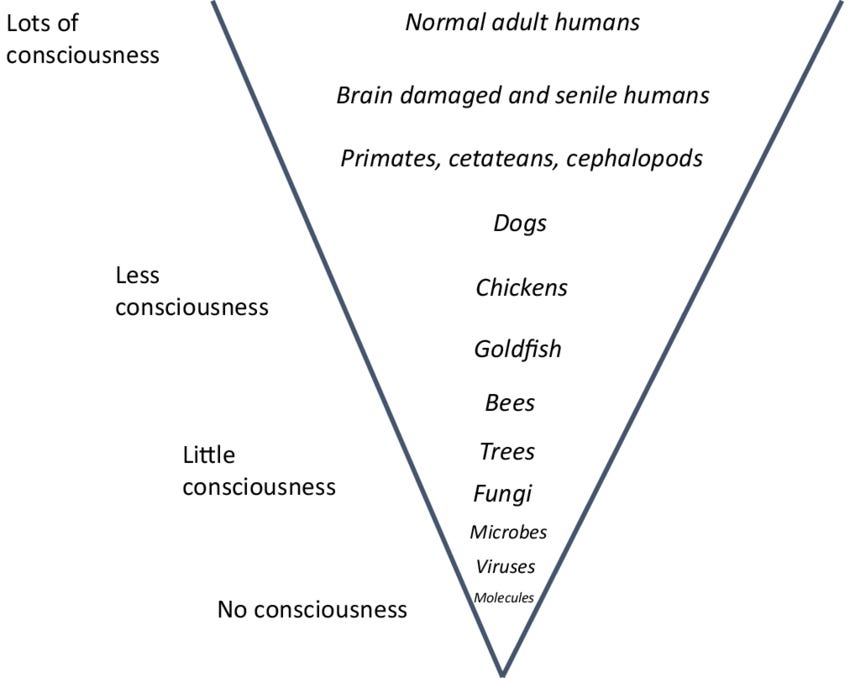

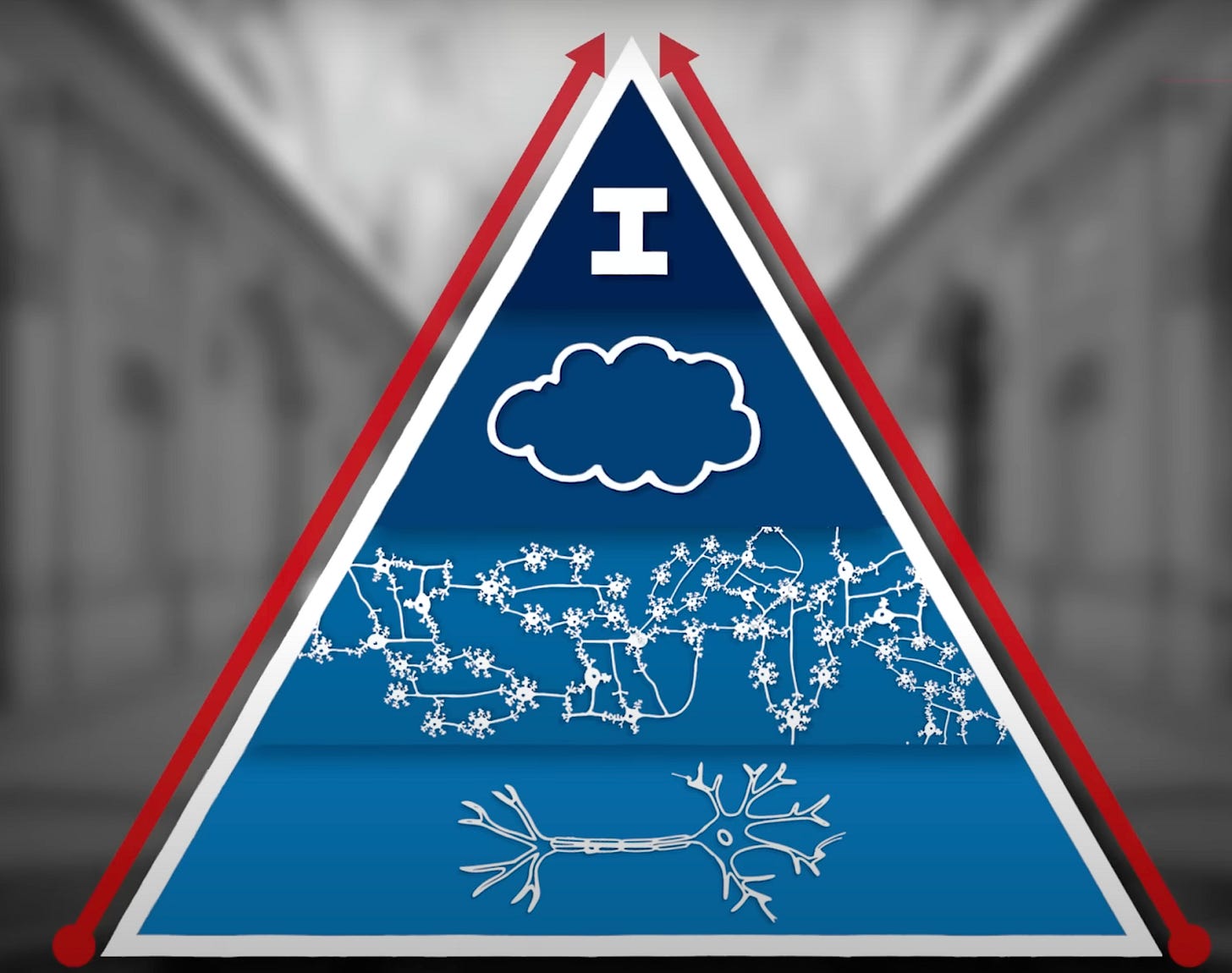

Below is Hofstadter’s consciousness abstraction pyramid.

Starting at the bottom are neurons, the lowest level. Above neurons are groupings of neurons called symbols, which represent standalone concepts. For example, when you see a dog, a group of neurons fire together, representing “dog”. The symbol for a dog is simply this group of neurons that activate when you see a dog. Groups of symbols make up thoughts, such as “Achilles walked his dog in the rain.” Lastly, at the top, there is “I”, which is a collection of thoughts that combine to form a sense of self – more on this later.

However, not all living things make it to the top of this hierarchy. The further up you go, the “more conscious” you are said to be. While everything is made up of atoms, not everything has neurons, less have symbols and thoughts, and even less have a sense of self. This results in a “consciousness hierarchy”.

Normal adult humans maintain a fully developed sense of self – which Hofstadter claims is the maximum degree of consciousness. But some humans have less than others, infants and the senile are two examples. Below that are dogs – do dogs have a sense of self? If a dog looks at itself in the mirror does it think “that’s me”? Maybe, what matters is the position relative to others. It doesn’t matter if a dog has a sense of self, but rather that it is less than a human and greater than a bee.

The idea of relativity within the hierarchy is important because it acts as a ranking of how much we care about something or someone. Why do you kill a buzzing mosquito but not a barking dog? Why are vegetarians ok with eating plants but not animals? Should the mentally ill be forced into institutions? Why do you cry when your dog dies but not your goldfish? These are all questions that deal with your consciousness hierarchy. We do things to beings on one level of the hierarchy that would be unthinkable at other levels.

Hofstadter’s intention when he introduces us to this concept is that consciousness is not binary, but gradient. Just as a dog's sense of “I” is less developed than a human, different humans have varying degrees of consciousness too.

Which brings us to “I”.

What does it mean for “I” to be at the top of the consciousness hierarchy? Just as understanding a heart's function transcends analyzing cells, grasping the essence of “I” cannot be done through neurological examination. This “I” synthesizes our actions, desires, and beliefs into a unified self-awareness, providing a philosophical foundation for understanding our very existence. Remember that the philosophical level deals with purpose, the purpose of a heart is to pump, whereas the purpose of our thoughts (aka desires, beliefs, etc.) is our sense of self.

Here is Hofstadter:

"Why did you ride your bike to that building?" "I wanted to practice the piano." "And why did you want to practice the piano?" "Because I want to learn that piece by Bach." "And why do you want to learn that piece?" "I don't know, I just do — it's beautiful." "But what is it about this particular piece that is so beautiful?" "I can't say, exactly — it just hits me in some special way."

This creature ascribes its behavior to things it refers to as its desires or its wants, but it can't say exactly why it has those desires. At a certain point there is no further possibility of analysis or articulation; those desires simply are there, and to the creature, they seem to be the root causes for its decisions, actions, motions. And always, inside the sentences that express why it does what it does, there is the pronoun "I" (or its cousins "me", "my", etc.). It seems that the buck stops there — with the so-called "I”.

If this “I” is responsible for everything that we do, it must exist, right? Hofstadter says no. Your sense of “I” is an illusion that acts as the necessary abstraction for us to understand our actions and desires. Just as the concept “pump” doesn’t actually exist, your sense of self doesn’t exist either, they are both just concepts that we use to understand and survive in the world. Remember that humans abstract to higher levels because we are unable to understand the lower levels. Our sense of “I” is an abstraction that allows us to understand our motivations.

Here is Hofstadter again:

In which the starring role, rather than being played by the cerebral cortex, the hippocampus, the amygdala, the cerebellum, or any other weirdly named and gooey physical structure, is played instead by an anatomically invisible, murky thing called "I" , aided and abetted by other shadowy players known as "ideas", "thoughts", "memories", "beliefs", "hopes", "fears", "intentions" , "desires", "love", "hate", "rivalry", "jealousy", "empathy", "honesty", and on and on — and in the soft, ethereal, neurology-free world of these players, your typical human brain perceives its very own "I" as a pusher and a mover, never entertaining for a moment the idea that its star player might merely be a useful shorthand standing for a myriad of infinitesimal entities and the invisible chemical transactions taking place among them, by the billions — nay, the millions of billions — every single second. [Humans] can't see or even imagine the lower levels of a reality that is nonetheless central to its existence.

III.

We now must take a short detour to describe a key concept in Hofstadter's work: the strange loop. Unlike a linear hierarchy where each level distinctly surpasses the previous (A > B > C), a strange loop creates a paradoxical circuit where the hierarchy loops back onto itself (A > B > C > A). A strange loop is a hierarchical structure where, as you move upwards or downwards, you eventually find yourself where you began.

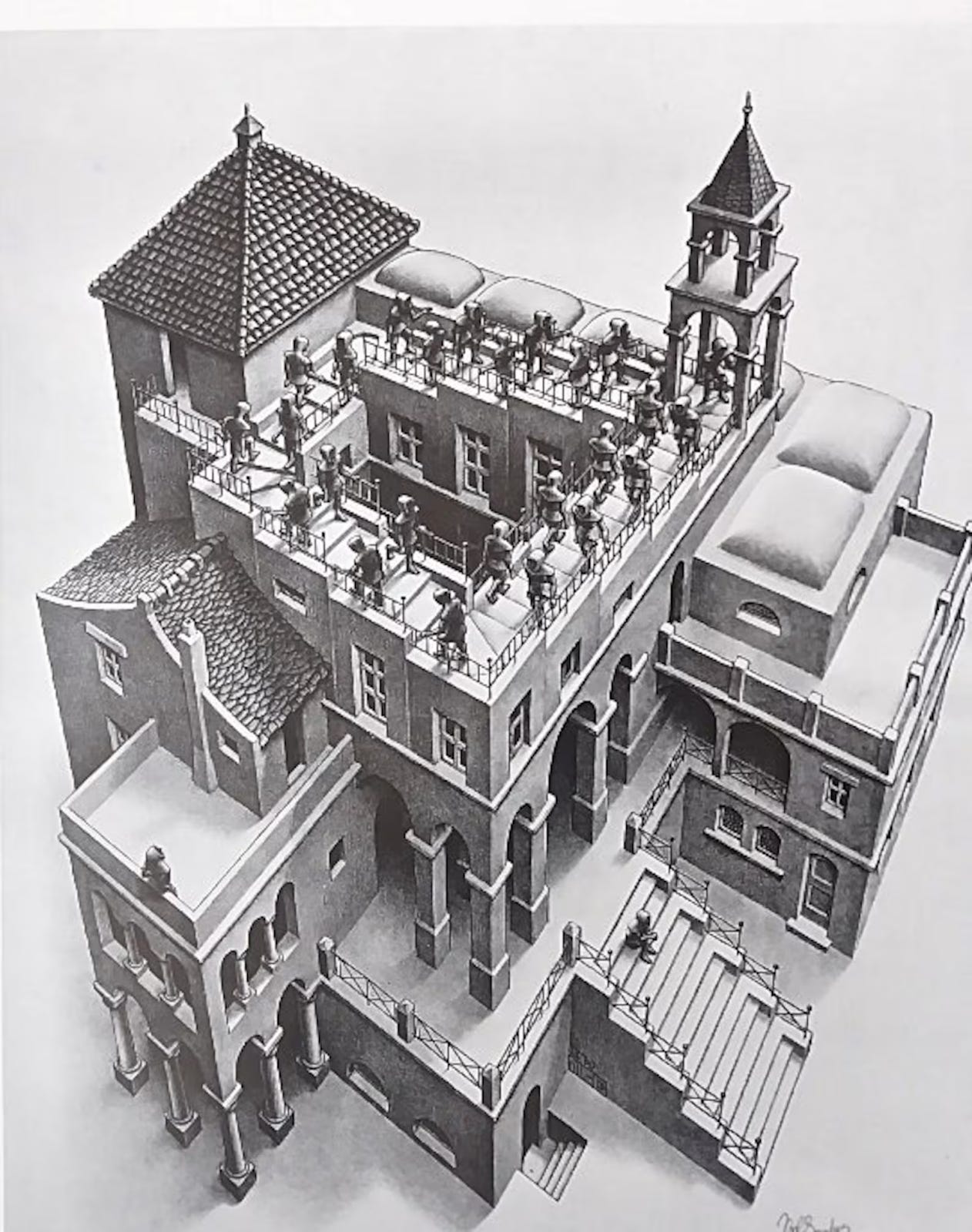

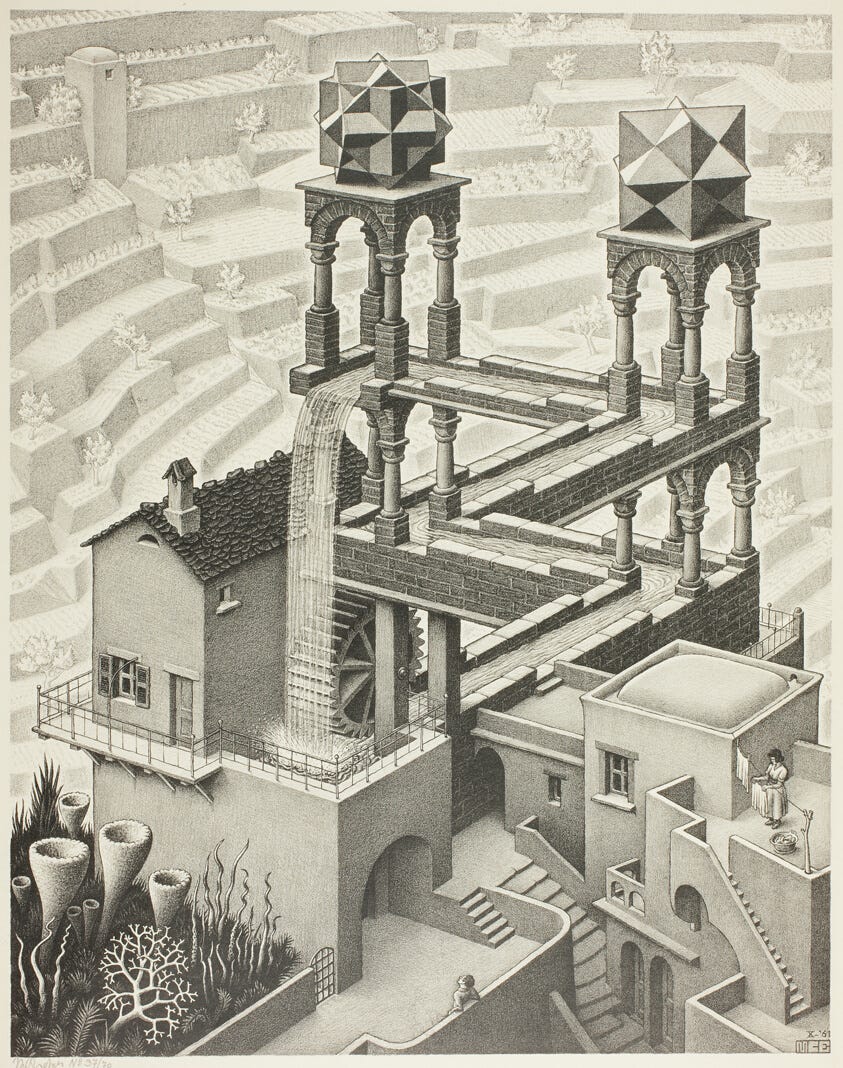

The best way to understand strange loops is through images. Below is a famous print by M.C. Escher called Ascending and Descending.

As you can see, as you move up or down the staircase, you eventually find yourself right where you started. Another visual example of a strange loop is Escher’s Waterfall, where the waterfall seems to flow into itself like a perpetual motion machine.

These images are useful in allowing us to visualize the concept of a strange loop. But the problem, of course, is that they aren’t real… But don’t worry, Hofstadter has identified some other, non-visual strange loops.

Take for example, the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. Hofstadter claims that in Bach’s The Musical Offering Canon 5 “continues to rise in key, modulating through the entire chromatic scale until it ends in the same key in which it began.”

You can listen to it here.

Since I have little to no musical background, especially in classical, and cannot verify this claim in the slightest, here is Hofstadter again from GEB:

What makes this canon different from any other, however, is that when it concludes - or, rather, seems to conclude - it is no longer in the key of C minor, but now is in D minor. Somehow Bach has contrived to modulate (change keys) right under the listener's nose. And has so constructed that this "ending" ties smoothly onto the beginning again; thus one can repeat the process and return in the key of E, only to join again to the beginning.

Another example of a strange loop is Kurt Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem, which I will now describe in grossly oversimplified terms. In 1931, Gödel embedded the phrase “this statement is false” into a mathematical equation. If the statement is true, then as it says, it's false. But if the statement “this statement is false” is false, then that means it's true. But if it's true, then it says it's false! Etcetera.

The astute reader may recognize this as the Liar Paradox, which has been around for thousands of years. Gödel’s innovation was that by embedding it into a mathematical equation, he was able to prove that formal systems like arithmetic have statements that are true but cannot be proven from within the system itself. This might seem like semantic nonsense, but Gödel’s Incompleteness theorem is considered to be one of the greatest intellectual achievements of the 20th century.

(Fun side bar on Gödel. When studying for his US citizen test, he found a loophole in the Constitution that would permit American democracy to legally turn into a dictatorship. He told his friends, including Einstein, about the existence of a flaw, but never the specifics. We still are not sure what he found. Gödel’s Loophole has been called “one of the great unsolved problems of constitutional law”.)

Despite Hofstadter spending more time on Gödel and his theorems than anything else, I actually find it non-essential to understanding the actual thesis of his books (particularly IAASL). That is, you don’t have to fully understand the incompleteness theorem beyond knowing that Gödel discovered a strange loop within the heart of mathematics.

We have now covered the titular triumvirate that is Gödel, Escher, and Bach. Congratulations. You now know more about GEB than most people – it is, in fact, not about the intersection of math, art, and music, but instead about proving the existence of strange loops through the works of these three men.

IV.

If the title of Hofstadter’s latter book didn’t give it away, we now get to his primary insight: you are a strange loop. Meaning your sense of self, the abstraction process through which you identify as “you”, and the interactions you have with the world, are the result of a strange loop occurring in your brain.

As your current “I” - an abstract illusion that acts as a collection of all your up-to-date desires and beliefs - interacts with the world, it causes a feedback loop that leaves you, after the interaction, with a slightly modified “I”. It is a paradox where our sense of self is derived from, but also drives, the lower levels of our existence. Neurons make up the desires that culminate in “I want that”, which in turn leads to the manipulation of atoms causing new neurons to fire.

What?

Imagine you decide you want to learn the guitar. This aspiration is the result of neurons made up of atoms, firing at once to create symbols and thoughts, culminating in “you” picking up and practicing the guitar. During your first practice session, you interact with the world in a myriad of ways: your fingers on the strings, the sounds of the strings, the feedback from a teacher or listener, and the emotional responses to playing. As we know, this is just atoms moving around other atoms, but these atomic movements lead to new neurons to activate in your brain, new symbols to form, resulting in thoughts that ever so slightly modify your concept of “I”. You no longer want to learn the guitar, you are learning the guitar. This is why experiences fundamentally change you, sometimes big, sometimes small.

Another example would be someone that maintains a daily journal. Their current desires and reflections are translated into the physical action of graphite being transferred from pencil to paper. If the author re-reads their entry a few years later, they may have some new experiences that react with the old entry to spark new ideas. The “I” from a few years ago arranged graphite lines on a piece of paper, which caused a future “I” to change. This is the strange loop. Your “I” changes atoms, which changes your “I”, which changes atoms… and so forth.

I quote Hofstadter:

And thus the current "I" — the most up-to-date set of recollections and aspirations and passions and confusions — by tampering with the vast, unpredictable world of objects and other people, has sparked some rapid feedback, which, once absorbed in the form of symbol activations, gives rise to an infinitesimally modified "I"; thus round and round it goes, moment after moment, day after day, year after year. In this fashion, via the loop of symbols sparking actions and repercussions triggering symbols, the abstract structure serving us as our innermost essence evolves slowly but surely, and in so doing it locks itself ever more rigidly into our mind.

Somehow, the world works in a way where atoms are just moving themselves around in a seemingly random way. Any “purpose” we could try to assign to these movements we have already determined to be an illusion.

We can now take this idea to its logical conclusion. If “you” are just a high-level abstraction of incomprehensible lower levels, and we all share these lower levels (my atoms are identical to your atoms), then it implies that your strange loop (your sense of self) can exist outside yourself.

Take for example anyone that you have lived with for a long time: parent, child, spouse, sibling, etc. The act of deeply knowing someone is to get a copy of their strange loop into your head as well. To understand someone else's desires and beliefs is no different than understanding your own. If you walk down the street and see something in a store window and your first thought is “wow, my wife would love this!”, you are experiencing someone else’s strange loop in your own head. The root desire is no longer “I like this”, but “they like this”.

The implication is that you – as defined by your beliefs, desires, goals, and aspirations – exist in dozens of other people! Of course, the strange loop that exists in others is not as strong as the “original”, but it still exists nonetheless. Above we discussed the fact that consciousness is gradient and not binary, and the same goes for strange loops. Hofstadter uses language as an analogy to the idea of duplicate strange loops. While you will never be a “native speaker” (like you are with your own strange loop), you can still become fluent. Here is Hofstadter talking about his wife, Carol.

Although it took me several years to learn to "be'' Carol, and although I certainly never reached the "native speaker" level, I think it's fair to say that, at our times of greatest closeness, I was a "fluent speaker" of my wife. I shared so many of her memories, both from our joint times and from times before we ever met, I knew so many of the people who had formed her, I loved so many of the same pieces of music, movies, books, friends, jokes, I shared so many of her most intimate desires and hopes. So her point of view, her interiority, her self, which had originally been instantiated in just one brain, came to have a second instantiation, although that one was far less complete and intricate than the original one.

Two people that have spent decades together not only maintain a well-formed version of the other's strange loop, but they also begin sharing one. In addition to deeply understanding each other's desires and beliefs, these desires and beliefs have fused into one. The book gets oddly romantic in a sort of nerdy, scientific way. Here is Hofstadter talking about his wife again.

We had exactly the same feelings and reactions, we had exactly the same dreads and dreams, exactly the same hopes and fears. Those hopes and dreams were not mine or Carol's separately, copied twice — they were one set of hopes and dreams, they were our hopes and dreams. I don't mean to sound mystical, as if to suggest that our common hopes floated in some ethereal neverland independent of our brains. That's not my view at all. Of course our hopes were physically instantiated two times, once in each of our separate brains - but when seen at a sufficiently abstract level, these hopes were one and the same pattern, merely realized in two distinct physical media.

When someone dies, the original strange loop goes away, but copies of them continue to exist in all those that knew them. Which gets us back to Hofstadter’s wife, who you may have noticed is referred to in past-tense. Carol died tragically from brain cancer when their children were toddlers. While this is unfathomably tragic, it also acts as a potential critique of his book: is this entire idea around multiple strange loops just a way for him to cope over the untimely death of his wife?

He addresses this concern head on and says that he was working on these concepts long before his wife passed. He is right, in a certain sense. GEB, which contains nearly all the building blocks that make up IAASL, was written years before he even met Carol. Despite this, it's impossible to say that some of the chapters in IAASL weren’t heavily influenced by her passing. And I wouldn’t expect them to be! As we have just seen, an event as large as that is certainly going to alter his strange loop in a dramatic way.

V.

I enjoyed both of these books for very different reasons. I Am A Strange Loop presents a well-structured, coherent theory of the mind. Even if you don’t fully subscribe to the theory laid out in the book, there is an array of tangential concepts that are intensely thought provoking.

On the other hand, Gödel, Escher, Bach is a completely different beast. It has achieved almost mythological status in our current zeitgeist. It is also perhaps the most common answer of the tech intelligentsia to “what is your favorite book?” Maybe true, but probably signaling.

That’s not to say it isn’t a very, very good book, but I cannot overstate the difficulty of reading it. This difficulty is what has given it longevity, GEB would lose its raison d'etre if it were ever tamed. If you want Hofstadter’s structured thesis, go read I Am a Strange Loop. If you want to be taken on a journey that, through its intellectual dead ends and fascinating-yet-irrelevant-to-the-main-point concepts, will challenge your mind and ever so slightly alter your strange loop, then read GEB. Part of the experience is dealing with its varying mediums, from dialogues to images to puzzles to pages of symbols. GEB is what you get when a young polymath decides to show off.

Most books are relaxing to read. GEB is the intellectual version of a marathon. With the strong link between mental exercise and neurodegenerative disease prevention, it may be prudent for doctors to prescribe chapters of GEB.

It will also take you a long time to finish. It is then fitting that Hofstadter invented a concept in GEB that describes the “difficulty of accurately estimating the time it will take to complete tasks of substantial complexity.”

I give you, Hofstadter’s Law: “It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter's Law.”