Where do they go from here?

Evaluating the historical sources of German nation identity.

I.

The story of German national identity goes something like this: German culture was an essential part of European history beginning in the High Middle Ages, yet politically it existed as a decentralized collection of kingdoms and duchies. We don’t see centralized unified German state until 1871, when Otto von Bismarck bucked this trend and achieved German unification. The young nation then found itself on the losing end of two world wars, the latter which saw it commit some of the worst atrocities in modern history. All of this was (rightly or wrongly) blamed on German national identity, which the post-war occupiers focused on eliminating. Having completely internalized their shame (much to the relief of the rest of the world), the Germans looked around at each other after reunification in 1990 and asked, "where do we go from here?"

Even 35 years after the Berlin wall fell, this is mostly where we’re at today. The 4th largest economy in the world, the de-facto leader of the European Union, has a national identity that is notably different than its peer nations. This essay is an attempt to evaluate the historical stories of Germany’s past to try and answer the question of how German national identity will evolve into the future. The source material for this essay consists of Germany: Memories of a Nation by Neil MacGregor, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William Shirer, Blood and Iron by Katja Hoyer, Aftermath by Harald Jahner, and After the Reich by Giles MacDonogh.

II.

In 1945, after six long years of war and much their country destroyed, the Nazi’s formally surrendered. It’s important to put into context what the allies were thinking at this moment: here is this relatively new country, formed through "iron and blood", that has, within a 25-year window, started the two greatest wars the world has ever seen combined with unconscionable atrocities. They tried a harsh treaty in 1919, which failed. They tried appeasement in 1938, which also failed. Germany was now under occupation, an opportunity that would not likely come again, leaving one chance to achieve the stated goal of "never again". The decision had to be made on what to do: should they split Germany back into a pre-1871 collection of independent states? or maintain unification but expunge all militaristic and nazi-oriented cultural elements? Despite the wishes of France, they chose the latter.

Step one of this plan was to target Prussia. Prussia was the largest and most well-known of the German states; Bismarck, Fredrick the Great, Wilhelm II, and Kant, were all from Prussia. Prussia was blamed for its highly militaristic culture, going back centuries. Voltaire famously quipped “where some states have an army, the Prussian Army has a state”, in reference to Prussian military expenditures, which neared 75% of state budget in peacetime. (For reference, in 2025 the US spent 11% of state budget on its military). Therefore, in February 1947, the allies decided to wipe Prussia off the map. The preamble to the declaration read:

"The Prussian State which from early days has been a bearer of militarism and reaction in Germany has de facto ceased to exist."

For reference, here are two maps of German states, one from 1920, another from 2025. You can see that while many states remain, such as Bavaria and Saxony, Prussia is nowhere to be found.

To this day, modern Germans do not hear about Prussia outside of history class or perhaps a walking tour of Berlin. The allies post-war objective was achieved in this sense — Prussia no longer exists.

Another "never again" tactic, championed by Churchill in particular, was the ethnic cleansing of all European Germans back to Germany. A surprisingly under discussed fact of post-WWII history is that between 1945 and 1950, 15 million ethnic Germans were expelled from eastern Europe and forced to resettle in Germany or Austria. The primary justification for this move was that it would help stabilize the region after the war and into the future.

In addition to eliminating the concept of Prussia and re-settling, the allies did extensive de-Nazification, re-education of brainwashed youths, and wrote a pacifist-oriented constitution to go along with a decentralized central government.

The post-war occupation of Germany was tremendously successful from at least one perspective: Germany has not invaded anyone since. The militaristic national identity of Germany was stripped away, which paved the way for a western-aligned economic powerhouse. But while the allies were successful in stripping away the old identity, it was up to the German people to come up with a new one. Let's now go back into history for potential sources of German national identity.

III.

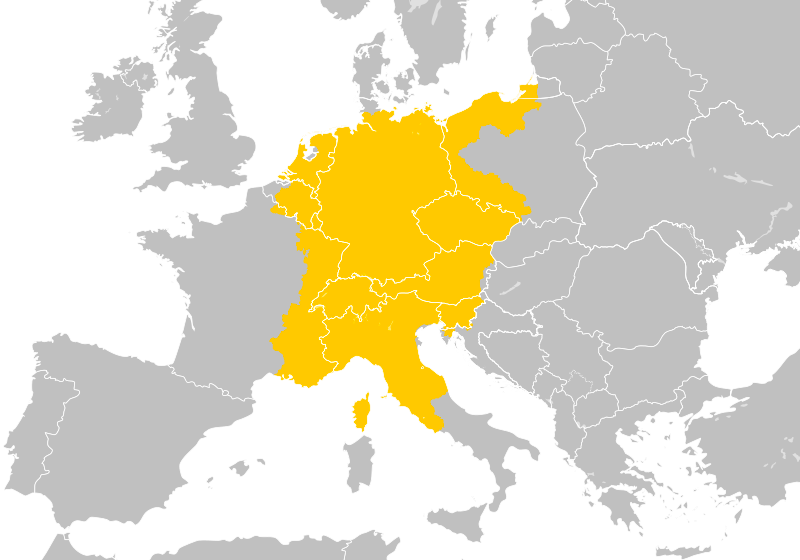

Even without any bad stuff, Germany has this problem where many of the people and places that could be used for their national identity are not within its modern borders. For this we can first blame the Holy Roman Empire. The Holy Roman Empire was famously "neither holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire"; instead, it was a loose collection of states that occupied most of central Europe for hundreds of years. The states that made up the Holy Roman Empire were mostly German, and many of them did not wind up within the borders of modern Germany.

Take for example, the oldest German university. Universities are a common source of national pride for intellectual achievements. Oxford was established in 1096 and has been a tremendous source of English exceptionalism. The same goes for the Sorbonne in France or Harvard in America. For Germany this is Charles University (Karls-Universität). This great university was created as the first German speaking university to compete with the Sorbonne. The problem with this quintessential German university? It’s in Prague and stopped speaking German after 1945. Would Harvard still be a source of American pride if it wasn’t in America and stopped speaking English? Or Oxford if it was in Ireland?

Or take the great city of Strasbourg, which rests upon the river Rhine. This city was home to perhaps the greatest of all German writers, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. It was also the residence of Johannes Gutenberg when he perfected his printing press. It’s now part of France.

What of the great German philosopher, Immanuel Kant? He was born in the Prussian city of Königsberg and literally never left. I don’t mean that he never lived anywhere else, I mean he basically didn’t take a single step outside the city for his 79 years of life. Today that city is called Kaliningrad and became Russian in 1945.

This phenomenon isn’t unique to Germany; many other countries have a similar situation: Istanbul for the Italians or Alexandria for the Greeks. But these are the exceptions that prove the rule - no country has so much of their cultural history living outside their modern borders as does Germany.

This phenomenon also applies to people as much as places. The most famous example is the founding father of the German people: Charlemagne. Charlemagne formed the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century and is considered "the father of Europe". When he died his empire fractured into east and west, which became the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of France, respectively. This kicked off a 1,200-year animosity between Germany and France about who gets to claim Charlemagne as their own. This was taken very seriously as many French kings would become anointed using Joyeuse, Charlemagne's sword, which now sits in the Louvre.

So, who gets to claim Charlemagne? If the name is any hint, the rest of the world considers him French, even if they don’t know it. Charlemagne is his French name; Germans call him Charles the Great. I suppose it's not impossible to form a national identity around contested figures, but what would it mean if another country had legitimacy to claim George Washington or Mahatma Gandhi as their own?

These historical facts may complicate the picture but are not without precedent. Germany unified in in the 19th century despite many of these same issues, how did they do it?

IV.

In 1871, a Prussian statesman named Otto von Bismarck successfully unified a collection of central European states into a modern German nation (if you want a full account of this, see my essay on Bismarck). Bismarckian identity was driven primarily by two factors: language and war.

Language

When trying to unify a collection of states, a common language is a great place to start. Luckily for Bismarck, the majority of those living within the Holy Roman Empire spoke German on a day-to-day basis. This was due to the widespread popularity of Martin Luther’s bible, which was famously written in everyday German rather than Latin, the language of the elites. Having a common language allows communication, trust, and written stories to help align independent states.

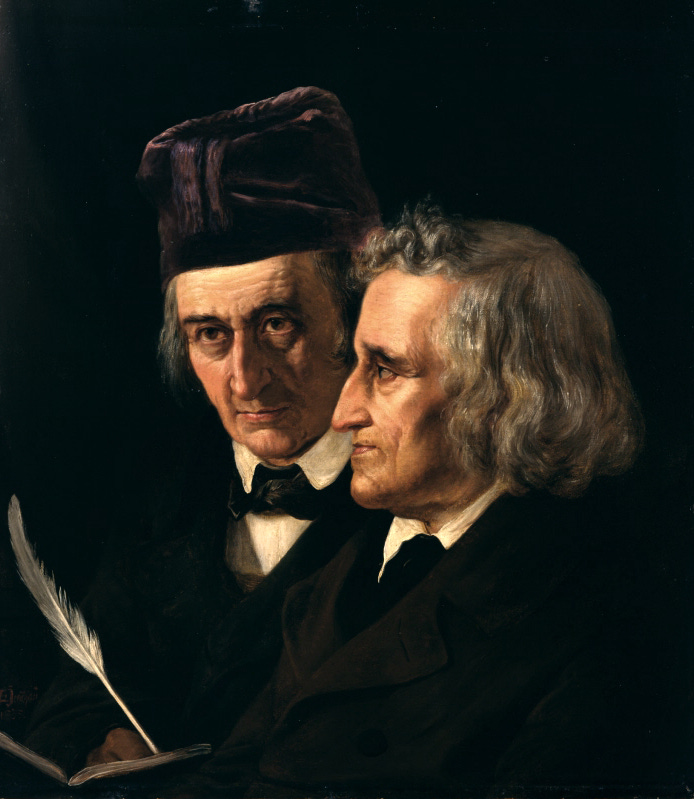

The best example of using German writing as a source of shared stories was the brothers Grimm, whose catalog of original and popularized works includes Cinderella, The Frog Prince, Hansel and Gretel, Rumpelstiltskin, Little Red Riding Hood, Rapunzel, Sleeping Beauty, and Snow White.

The brothers were tremendously important for their contribution to the formation of German identity. They were writing in the early 1800s which was a tumultuous time for all of Europe, but especially for the German states. Napoleon’s conquests had ended the Holy Roman Empire for good, organized religion was in steep decline, and nationalism was spreading across Europe. These factors caused the German states to ask themselves, "what are we? what does it mean to be German?" There wasn't yet a great answer, aside from "definitely not French".

The brothers’ stories greatly developed German culture, helping form the basis for Bismarck's Germany.

However, the brothers Grimm were re-evaluated after 1945. Their lesser known, antisemitic tales were held up by the Nazis as a source of great pride, which tainted their entire canon. MacGregor adds:

In consequence, the [Grimm] stories were for a later generation stained not just by this official [Nazi] endorsement, but by a concern that the violence and cruelty in the tales might also be an enduring trait in the national character, and one not always redeemed by traditional German virtues.

Defense & Militarism

If there are any laws of history, one would be that war unites people. While a shared language and culture may be a prerequisite for unification, it’s rarely the catalyst. Instead, it's war that binds a nation together. This is especially true for defense: small independent states are much easier to conquer than large, unified ones. Countries that unified for defensive purposes include Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Malaysia, any country with "United" in its name", Belgium, Netherlands, Japan, and many more. It's almost harder to find countries that didn't originate this way.

You only need to read the lyrics of various national anthems to get a sense of the importance of war in shaping national identity. Here is the Malaysian national anthem, Negaraku, which is largely about defensive unification:

My motherland,

The land where my blood spills,

The people live,

United and progressive!

Or take the The Star-Spangled Banner. While everyone is familiar with “And the rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air,” the lesser-known latter verses of get even more descriptive: "Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps' pollution."

Although my favorite example is the French National Anthem, La Marseillaise, which is almost comically violent.

The blood-stained standard is raised,

Do you hear in the countryside,

Those blood-thirsty soldiers ablare?

They're coming right into your arms

To tear the throats of your sons, your wives!

To arms, citizens,

Form up your battalions

Let's march, let's march!

Let blood impure

Water our furrows!

And who might those “blood-thirsty soldiers” be? The Germans, of course.

With that in mind, it should come as no surprise that the German unification in 1871 was initiated through war against France. Bismarck tricked Napoleon III into attacking, which spurred nationalistic fervor amongst the German states, allowing him to unify. Here is a speech Bismarck wrote admitting the path to unification was to be done not through speeches, but through war, giving him the nickname "The Iron Chancellor".

The position of Prussia in Germany will not be determined by its liberalism but by its power [...] Prussia must concentrate its strength and hold it for the favourable moment, which has already come and gone several times. Since the treaties of Vienna, our frontiers have been ill-designed for a healthy body politic. Not through speeches and majority decisions will the great questions of the day be decided—that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849—but by iron and blood.

But while Bismarck's greatest achievement was unifying Germany, his greatest failure was the trajectory it took once he was gone. The national identity of Bismarck’s Germany melted away after 1918 and 1945. Germans now have a high aversion to anything that even remotely smells of militarism. Look no further than the Hermann Monument, built in 1875 as a symbol of Arminius’ victory over the Romans, which is now looked at as cringey at best, shameful at worst. There are many that don't want stories like this being included in the German identity. In 2009, the 2,000-year anniversary of the victory, there was no parade or celebration held in Germany. There were, however, celebrations in the town of Hermann, Missouri. Go figure.

V.

With all that, where could German national identity go in the 21st century?

If there is one area where Germany is certainly leading the world, and I believe to be a source of their new national identity, is owning one’s mistakes. There are few countries that have erected monuments in the middle of their capitals dedicated to their own shame. Yet in the heart of Berlin, only a few hundred yards from the Reichstag, is the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. There are other friendly modern nations with genocidal pasts (Turkey and Japan) that, to this day, won't even acknowledge them. It may seem paradoxical to list shame as a source of national pride, but I think this works in a “more enlightened than thou” sense.

Modern German national identity is also greatly bolstered by how they view themselves economically. It was Germans that invented the printing press, the car, and the diesel engine. It's Germany that is the economic powerhouse of Europe, with a reputation of intense dedication to quality and industriousness.

Germany’s national identity is also strongly tied to the EU project. Rather than focusing on past national glory, it emphasizes building a peaceful and united Europe. It’s about looking forward rather than back. If anyone is right for the task it's Germany, who's history is tied to an entity that operated similarly: the Holy Roman Empire.

Although there is a degree to which Germany's de-militarized, and fluid national identity is due to the 70 or so years we’ve lived in a unipolar world. Germany didn't need a military (or a strong national identity for that matter) because the Americans were guaranteed to keep the peace. But times are changing. As the US pulls back from Europe, Germany has begun to rearm. Will this lead to a reinvigoration of Germany's historical stories that were much maligned post-1945? Or will the future looking, peaceful, European economic juggernaut narrative keep hold?

I'm also not so cynical to think that this is a binary choice. Yes, it is possible for Germany to rearm itself and use history as sources of national identity, without trying to conquer Europe and set up death camps. This could be the only outcome that leads to a unified Germany into the future. When times get tough and foreign dictators come knocking, you need to look backwards for inspiration to move forward. To quote Goethe, "He who cannot draw on 3,000 years is living hand to mouth.”

Great article, especially after being in Berlin last year and seeing the tributes to the victims of the Holocaust.