The Iron Chancellor

Otto von Bismarck and the country he created

In the annals of statecraft, few names stand as tall as Otto von Bismarck. Known as the 'Iron Chancellor', he was the mastermind who maneuvered through war and diplomacy to unify a divided land, leaving a lasting imprint on world history.

Bismarck achieved what hadn't been accomplished in a millennium: the unification of his homeland. But what elevates him above your average unifier was that the country he created… was Germany. Depending on where you put the causality, without Bismarck you likely don’t get either world war, because without Bismarck you don’t get Germany.

Bismarck is easily in contention as the greatest statesman of all time. But don’t take it from me, biographer and historian Jonathan Steinberg says Bismarck pulled off “the greatest diplomatic and political achievements by any leader in the last two centuries.”

Born in 1815, Bismarck’s world was much different than the one we know today. Instead of a country called “Germany”, there was a collection of smaller states existing in central Europe. These states had some similarities, the big one being their language, but they also had substantial differences in their cultures and religions. The “German Question” was the name for the ongoing debate during the 1800s about how to finally achieve unity.

The entirety of German history before the 19th century can be viewed through the lens of unification. Whatever tribes, kingdoms, or states that existed at the time would occasionally unify for their collective military goals, but they would eventually devolve back down to self-rule.

One of those unification attempts was the political entity known as the Holy Roman Empire, which lasted for 1,000 years. The Holy Roman Empire sounds a lot cooler than it was, the famous quip is that it was neither Holy, Roman, nor an Empire. Instead, it was just a loose network of alliances where inter-state rivalries prevented centralized power from ever accruing. Sometimes these rivalries were fostered by France, who really did not want a huge unified German state to their only exposed flank.

Speaking of France… Napoleon was the one who ended the Holy Roman Empire when he conquered most of Europe by 1814. However, when Napoleon eventually lost and his armies retreated back to France, the war-torn German states realized they needed to organize themselves better in order to prevent any future invasions. So, in 1815 the successor to the Holy Roman Empire was born, the German Confederation.

The German Confederation was a little better than the Holy Roman Empire, but not by much. One problem was that in order to pass an important decision, all 39 states had to unanimously agree. Remember that the original government of the independent American colonies, the Articles of Confederation, failed for similar reasons. Whenever you have a group of states, they never want to give up their autonomy to a higher central authority, but not having a strong enough central authority leaves the confederation impotent and ineffective. The US states had an easier time giving up power than the German states, as it is much harder to give up self-governance after you have been doing it for a thousand years!

In addition to the unanimity issue, there was also a high degree of inter-state competition within the German Confederation. The two largest states, Prussia and Austria, were constantly competing over who controlled the confederation. This eventually led to a civil war in 1866 where member states allied with one of the two belligerents.

Prussia being one of the most militaristic states ever, has no issue defeating Austria. Most of the time Prussia was spending 65-80% of state revenue on the military. US military spending by comparison, which is considered relatively high, is around 18%. Voltaire famously said, “Where some states have an army, the Prussian Army has a state.”

While the war marked the end of the German Confederation, Prussia formed the uniquely named North German Confederation, which consisted of all the states that fought alongside it during the war. The southern states that allied with Austria were left alone, and Austria was fully out of the picture.

While they no longer cared about Austria, Prussia and the rest of the North German Confederation had forgiven the southern states for fighting against them and wanted them to join their union. The Prussian leaders badly wanted a unified Germany for a couple of reasons. First, was to be able to compete better with the French and the Russians. But the second reason was not about economics or power, but about nationalism. Here is a quote from historian Katja Hoyer, author of the book Blood and Iron:

Since the end of the Second World War, the word 'nationalism' has become so associated with right-wing politics that it is worth reminding ourselves that the form it took in nineteenth-century Europe was heavily coloured by liberal and romantic ideals. Like the Brothers Grimm, many believed there was beauty in national culture, identity and language.

Remember, the mid 1800s was a time of toppling monarchs and the introduction of the modern nation state. Of course romantic nationalism was on the rise. In fact, you could say it was even necessary as people transitioned from the idea of divine rule to rule of the people. The German states felt this especially strongly, because unlike the other powers of Europe, their people shared a language and culture but did not have their own country! As I said above, there is literally a term for this: the German Question.

This all sounded great, but the southern German states weren’t that interested in unifying with Prussia and the rest of the northern states. Perhaps the biggest reason for this was religious differences. The Reformation had divided the German states with majority Protestant in the north and Catholic in the south. The southern Catholic states were concerned that by joining the North German Confederation they would be the minority religion and be oppressed (which was a valid concern because that is exactly what happened).

The North German Confederation was now faced with a challenge: how could they unify with a group of states that didn’t really want to join? Military occupation would have been easy, but forcing unwilling states into a union rarely leads to a long and fruitful relationship. Additionally, despite their differences, the German states saw each other as one-people, and would unlikely have been able to justify German on German fighting. They needed to get the southern states to want to join.

Enter Bismarck.

The Unification of Germany

Bismarck at this point was leading the North German Confederation and knew that the best way to get the southern states to join with the north was through war. His public rhetoric was consistent with this line of thinking, here is an excerpt from 1862: “Not through speeches and majority decisions will the great questions of the day be decided… but by iron and blood.”

Bismarck did not mean war in the sense of invading the southern states, nor did he mean joining with the southern states in a war of aggression against a different country. By war he meant defense. Only in defense would the southern states be willing to band together with the north.

One way to start a war of defense is to keep yelling insults at your neighbor until they punch you in the face. Bismarck decided that the obvious neighbor to insult was their mortal enemy, France. Although, instead of explicitly insulting them for eating frog legs and snails, or whatever, Bismarck knew he needed to be more subtle. He didn’t want the French to know that he was trying to start a war. Luckily for him, an opportunity presented itself that he would famously take full advantage of.

Spain had just had a revolution where they overthrew their current monarch and then offered the crown to Prince Leopold. Leopold happened to be closely related to the current Prussian King Wilhelm I. At first, Leopold was going to decline the offer, but after pressure from Bismarck he accepted.

The French did NOT like this. Remember that they absolutely hated (hate?) the Germans, and now they were about to have a very Prussian monarch ruling the country to their southern border? That’s gonna be a no from me, dog. France proceeded to send a telegram to Wilhelm demanding he withdraw Leopold’s candidacy, renounce any claim to the Spanish throne forever, and publicly apologize to France.

Wilhelm, who was a firm but amicable guy, told Bismarck to politely decline the French offer. Bismarck seized his chance and wrote an altered, more disagreeable summary of Wilhelm’s message, and proceeded to leak it to the press. The French public felt insulted by the message and wanted to fight, within days Napoleon III mobilized his country for war. Just as Bismarck planned, this stirred up German nationalistic fervor and brought the southern German states right into his arms.

The war, known as the Franco-Prussian War, was expected to be a bloody and long conflict, but it would not be so. The Germans took Paris within six months, stunning the French and all neutral observers. Bismarck drafted a new constitution that included all the German states (but still no Austria) and Wilhelm accepted his new role as the emperor of the German Empire. And on that day, in 1871, Germany was born.

With Germany unified, Bismarck soon faced a bigger challenge: keeping it unified. Here is Hoyer again:

Bismarck could not make disappear the stark cultural rifts of a people that had been fractured for so long. Differences of regional loyalties, culture, custom, dialect, religion, history and (increasingly) social status would eventually fade and be replaced by a carefully managed concept of nationhood.

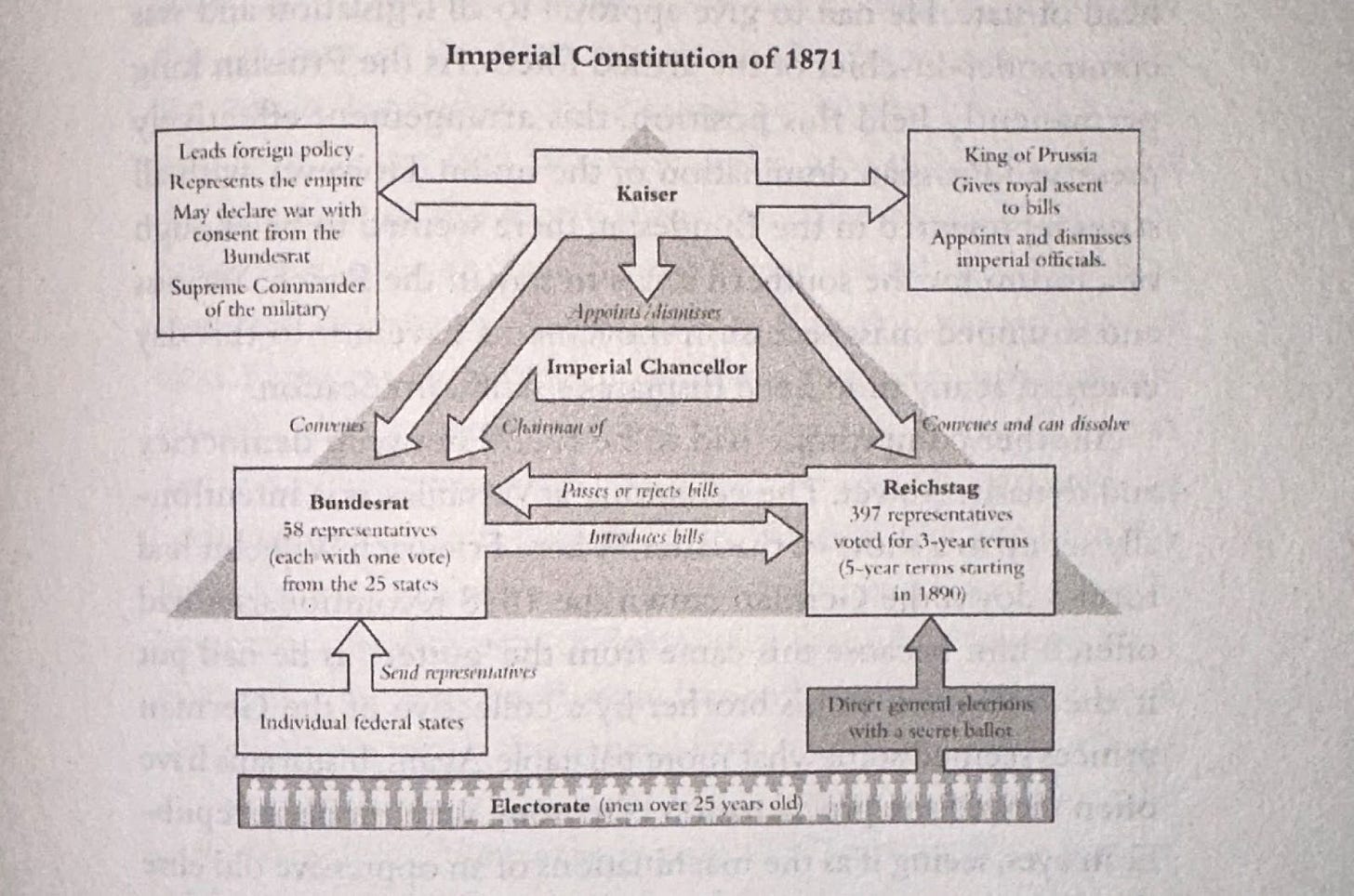

Part of this meant making sure that each state felt like they had proper representation in the new government. (This should sound familiar if you are familiar with US history). Below is a graphic showing how the new government was structured. My apologies for the bad quality, this comes directly out of Blood and Iron, and I couldn’t find a high-res image on the internet.

The Bundesrat and the Reichstag were very similar to the US Senate and House of Representatives, respectively. This seems to be the time-tested compromise between smaller and larger states. The big difference between most modern democracies though was the presence of the Kaiser, who would continue to be chosen by male-preference primogeniture from House Hohenzollern.

There were a lot of other things that Bismarck did to maneuver his way around the differing interests of states - a lot of backroom dealmaking and such. I won’t go into those here, but relevant to this is his famous quote: “Laws are like sausages, it is better not to see them being made.”

Let’s now look at some of Bismarck’s other achievements post-unification.

Economy

The German empire saw a staggering amount of economic growth right from the outset of unification. Bismarck did a few things that may have helped. He established a single currency, standardized measurements and weights, expanded the railways, and signed trade deals with other countries. He also helped get Germany’s literacy rate to 99%, one of the highest in the world.

Another important thing that he did for the German economy, being a laissez-faire capitalist, was to leave it alone. Throughout Bismarck’s time as chancellor, there was nearly no regulation of financial or business conduct. Being a highly educated, well-connected country during the industrial revolution means you didn’t have to do much in order to see tremendous economic growth. This of course led to some of the not-so-good parts of unfettered capitalism: worker exploitation and horrible working conditions. Combined with the fact that Karl Marx was from Prussia, a German socialist counterforce (called the Social Democrats) quickly grew.

The capitalist that he was, Bismarck was fearful of the rise of socialism. While the German constitution ensured that he couldn’t outright outlaw the party, he tried a few workarounds to hamper their success. These workarounds included: banning trade unions, socialist literature, and party organization events. Despite these efforts the Social Democratic party continued to grow.

You may be wondering why I included failed suppression tactics as “one of Bismarck’s other achievements”. Well, it's what he did next when he realized his original plan wasn’t working.

Bismarck began trying to win the support of the socialists by passing legislation that they would be interested in:

Sickness Insurance Act of 1883: provided up to 13 weeks of sick pay

Accident Insurance Act of 1884: workers comp, funded by employers which incentivized them to make the workplace safer

Old Age and Disability Act: pensions to those over 70 and to those that couldn’t work (social security)

This is actually insane. Remember that these types of programs did not exist anywhere in the world. While they weren’t the first instances of welfare - the Romans were famous for feeding the poor with excess grain - these laws were the foundation of modern welfare. This was also the first time worker’s compensation was put in place.

(On a side note, if you have spent any time learning about health care systems, you would have run into one called the “Bismarck model”. Which, depending on who you ask, has some of the best outcomes of all the different systems. Austria, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, and of course Germany, use Bismarck models.)

Did Bismarck actually believe in these measures? Or was he just being a shrewd statesman by wheeling and dealing favors to opposing parties? This speech of his says that he did at least believe in the concept of welfare:

The whole problem is rooted in the question: does the state have the responsibility to care for its helpless fellow citizens, or does it not? I maintain that it does have this duty [ . . . ] There are objectives that only the state in its totality can fulfill. [ . . . ] Among the last mentioned objectives [of the state] belong national defense [and] the general system of transportation. [ . . . ] To these belong also the help of persons in distress and the prevention of such justified complaints as in fact provide excellent material for exploitation by the Social Democrats. That is the responsibility of the state from which the state will not be able to withdraw in the long run.

Of course, this speech could also just be him politicking, but historian A. J. P. Taylor thinks otherwise.

It would be unfair to say that Bismarck took up social welfare solely to weaken the Social Democrats; he had had it in mind for a long time, and believed in it deeply. But as usual he acted on his beliefs at the exact moment when they served a practical need.

What do we make of this? On one hand we had a laissez-faire capitalist who banned socialist books, but on the other hand implemented the first of its kind modern welfare legislation. This is a great example of how the world doesn’t actually partition the way it does via modern US politics. Bismarck did not see a contradiction between lightly regulated business and providing welfare to the citizens of Germany.

Foreign Policy

Bismarck’s foreign policy was very deliberate in its goal: to preserve the fragile new nation of Germany. He was dealing with enough headaches at home, there was no reason to provoke any external ones too. Bismarck knew the other European countries were eyeing Germany suspiciously, so he was intentional in stressing to them that he was not interested in taking territory, and that the “German Question” getting answered did not mean a reshuffle of European power relations.

But of course it meant a reshuffle of power relations. Germany became, overnight, the most powerful European country! They had the biggest economy, the largest population, and were led by the aggressive and militaristic Prussians. This was obvious to all of Germany’s neighbors, specifically France, who saw right through Bismarck’s appeasements and freaked out.

Quick sidebar - I know I keep saying “and France freaked out”, but it really was true, and you only need to look at their geography to see why. They are well protected by mountains to their south and southeast and by water to their west and northwest. But their northeastern border with Belgium and Germany has no natural borders at all (after WW1 they even tried to make one). This was why they wanted to prevent a unified Germany more than anything and were very perturbed when it eventually came to be.

What would you do if your mortal enemy grew 12 inches, gained 100 pounds of muscle, and developed cauliflower ear? You’d call your friends for backup. France released a joint statement with Britain and Russia saying that no German territorial expansion would be tolerated in Europe. Even though this was just confirming exactly what Bismarck said - that he had no territorial ambitions in Europe - the statement was still unsettling to him. Some French generals had been vocally talking about a war of revenge against Germany for the Franco-Prussian war. If that was something that would eventually happen, Bismarck needed to be sure that Britain and Russia were also not against him.

To counter this threat from France, Bismarck decided… actually, let me just have him explain: “The secret of politics? Make a treaty with Russia.” However, he knew that any public treaty would ruffle France’s feathers, so he formed a secret pact with Russia saying that they each agreed to remain neutral if the other was to be attacked by a third party. The biggest fear of Bismarck (along with all subsequent German generals) was fighting a two-front war against France and Russia. Fighting one at a time was fine but fighting both needed to be avoided at all costs.

The secret to Bismarck’s foreign policy was he carefully studied the national interest of other countries and used that information to avoid conflict. Where national interests overlapped with Germany, he would make a mutually beneficial deal. Steinberg again:

In international relations, it meant absolutely no emotional commitment to any of the actors. Diplomacy should, he believed, deal with realities, calculations of probabilities, assessing the inevitable missteps and sudden lurches by the other actors, states, and their statesmen. The chessboard could be overseen and it suited Bismarck's peculiar genius for politics to maintain in his head multiple possible moves by adversaries....He had his goals in mind and achieved them. He was and remained to the end master of the finely tuned game of diplomacy. He enjoyed it. In foreign affairs he never lost his temper, rarely felt ill or sleepless. He could outsmart and outplay the smartest people in other states.

In fact, Bismarck’s view of the political landscape was so strong that he knew how World War I was going to start, 26 years before it did. In one of the more prescient quotes of all time: “One day, the great European war will come out of some damned foolish thing in the Balkans.”

Bismarck’s record on foreign policy during his tenure can only be described as successful. His goal was to use diplomacy and treaties to preserve peace on a very violent continent, which he was able to do.

Bismarck’s Blunders

Bismarck’s biggest blunder, which he would also probably admit, was how he handled the situation with the Catholics.

Remember that the southern states were very Catholic, and the northern ones were very Protestant. Although they joined Germany, the southern states were still highly skeptical of being in a Protestant empire. What scared them even more was the growing secularism in Europe after the French Revolution with the separation of church and state. Bismarck knew that the biggest cultural rift in his Empire was religious divisions, and he did not want that to be the reason Germany split again. Combined with the fact that Germany’s enemies were Catholic (France and Austria) and the sheer number of Catholics in Germany (37% of the population), he became increasingly concerned that the Catholics would conspire against the Empire.

Bismarck was correct about this concern, but the way he handled it was bad. His plan was to separate church and state and clamp down hard on the Catholics. Below were some of the actions that were taken:

Prohibition of any public statement by priests in political affairs. This led to the imprisonment of an archbishop

Outlawing the Jesuit Order (the most hardcore Catholics) across the entire empire

Forced education of the clergy to go under state control and made ecclesiastical positions require passing a state sanctioned test and approval

The first result of these measures was to increase the religious fervor of the Catholics. I feel like nowadays we have learned the lesson that religious repression tends to have the opposite effect, but that was not clear to Bismarck. Second, these laws (specifically the education one) also affected and therefore angered the Protestants, who were the core of Bismarck’s support. The end of these laws came with the rise of socialism, which Bismarck saw as a greater threat, and realized he needed Catholic support to prevent it.

This situation was very similar to the one with the socialists: Bismarck had an enemy, he tried to snuff them out, it ended up backfiring, so he changed plans and corrected course. The course correction was better in the case of the socialists, but his ability to update his strategy based on new information was admirable and very Bayesian indeed.

The Fall of the Iron Chancellor

The end of Bismarck’s reign coincides with perhaps his greatest blunder: the government he created. Bismarck was a traditional monarchist who made sure that the Kaiser had a lot of power in the government. There were some checks and balances from the Bundesrat and the Reichstag, but not many. The Imperial Chancellor position, which Bismarck held, was appointed by the Kaiser and essentially acted as a proxy - if the Kaiser wanted a proxy. If the Kaiser wanted to delegate, then the chancellor had a lot of power, but if he wanted to rule, then the chancellor was mostly a powerless position.

The Kaiser-chancellor relationship was designed by Bismarck around his relationship with Wilhelm I. Wilhelm didn’t really care about politics, so he delegated almost everything to his Imperial Chancellor. This worked great because Bismarck could call all the shots, while still having a Hohenzollern monarch at the “head” of the government.

However, when Wilhelm I died in 1888, his grandson Wilhelm II (who I will call “Willy” to avoid confusion) took over. The problem was that Willy was nothing like his grandfather. He was a young, ambitious ruler who desperately wanted to make a name for himself, which meant he did not delegate much to his chancellor. In 1890, nineteen years after he unified Germany, Bismarck was forced to resign by the new Kaiser. He spends his remaining years writing memoirs and taking pot shots at Willy, until his death in 1898.

Bismarck had a lot to say about Willy: “a hothead [who] could not hold his tongue, was susceptible to flatterers, and was capable of plunging Germany into a war without knowing what he was doing." Yet again, despite the personal animosity, Bismarck was correct. Willy did eventually plunge Germany into a war against both Russia and France, something Bismarck would have never done. While World War I did not spell the end of a unified Germany, it was the end of the government that Bismarck created.

In hindsight his blunder was obvious, our modern sensibilities understand why hereditary monarchies (even limited ones) are bad - you are guaranteed to get a dud who ruins everything. On top of that, his inability to create a true democracy (if that was even possible in Germany at the time), may have caused the World Wars. While it may be too far to blame Bismarck for the World Wars, we can perhaps fault him for knowing one was coming and not doing more to prevent it.

Despite his government only lasting 47 years, the unified country he created has lasted 152 and counting. Does Bismarck deserve credit for this at least? I think so. The leadership of a country during its fragile early years is what forms the institutions and norms that allow it to last for centuries. Just as George Washington laid the bedrock for national identity during his first two terms as president, Otto von Bismarck did the same for Germany, with repercussions that we still live with today.

you are sooo smart I think you got switched at the hospital. These pieces are incredible

I'm hangin with you this entire trip- well maybe not at night- but I want to hear everything you have to say.

I am SO proud of you!!!!!! You make my heart burst with pride! And love!