Not-a-Book Review: Love Island

What is it and why do we like it?

I.

I never thought I’d write about a reality TV show, but I found myself getting more engrossed into Love Island than I was Succession or Severance (both of which I enjoyed immensely). Which got me thinking… why? Sigmund Freud once said that “it is impossible to overlook the extent to which civilization is built up upon a renunciation of instinct.” And while I am normally good at renunciation, it turns out that Love Island caters to pure instinct.

Didn’t the wisest man in Athens say something about how the unexamined reality show wasn’t worth watching? If so, then I happen to agree.

Love Island is technically a dating show. Originally British, it has since spawned versions across the Anglosphere with Love Island: US and Love Island: Australia. The premise is simple: place attractive twenty-somethings into an isolated villa without phones or alcohol for eight weeks, watch them couple up, continuously introduce increasingly attractive newcomers, and crown the last couple standing as the winners.

Love Island stands out from most dating shows because it’s relatively unstructured. For the most part, contestants just mingle for every waking hour (reportedly getting quite bored), while cameras record everything. The producers then sift through hundreds of hours of daily footage, pulling out the storylines complete with rising tension and carefully timed reveals.

The show begins with ten contestants (called islanders) - five men and five women - who are put into “Couples”, which is the central dynamic of the show. Being in a “Couple” provides safety from being “dumped from the island.” It’s important to note that a “Couple”, as defined within the rules of Love Island (in which I will use a capital “C”), may or may not match the everyday meaning of a small-c couple, aka, an actual relationship. On the Island, contestants can be in a Couple without being a couple, and they also can be a couple without being in a Couple. However, both mismatches tend to be temporary since failing to form a romantic Couple typically results in being dumped from the island.

Each week there is a formal “re-coupling” where the Couples are re-made by allowing one set of contestants to pick who they want their new partner to be. Many times, this leads to the same Couple as before, but sometimes it forces the islanders to make tough decisions. Early on, contestants leave the show by being the last person standing after a re-coupling. It’s a lot like musical chairs… if everyone playing was a model. As the season progresses, you eventually end up with fewer and fewer couples, with the winners determined by viewer voting.

Contestants unable to secure strong partnerships get eliminated, new attractive participants are added into the villa, and each week’s re-coupling allows contestants to update based on the events of the previous week.

The entertainment value of the show revolves around the tension of whether couples stay together or not. Remember, any couple that exists in the villa is, at most, just a few weeks old, which inevitably leads to a lot of turnover. The peak of this tension is when the risks and stakes of breaking up are both at their highest.

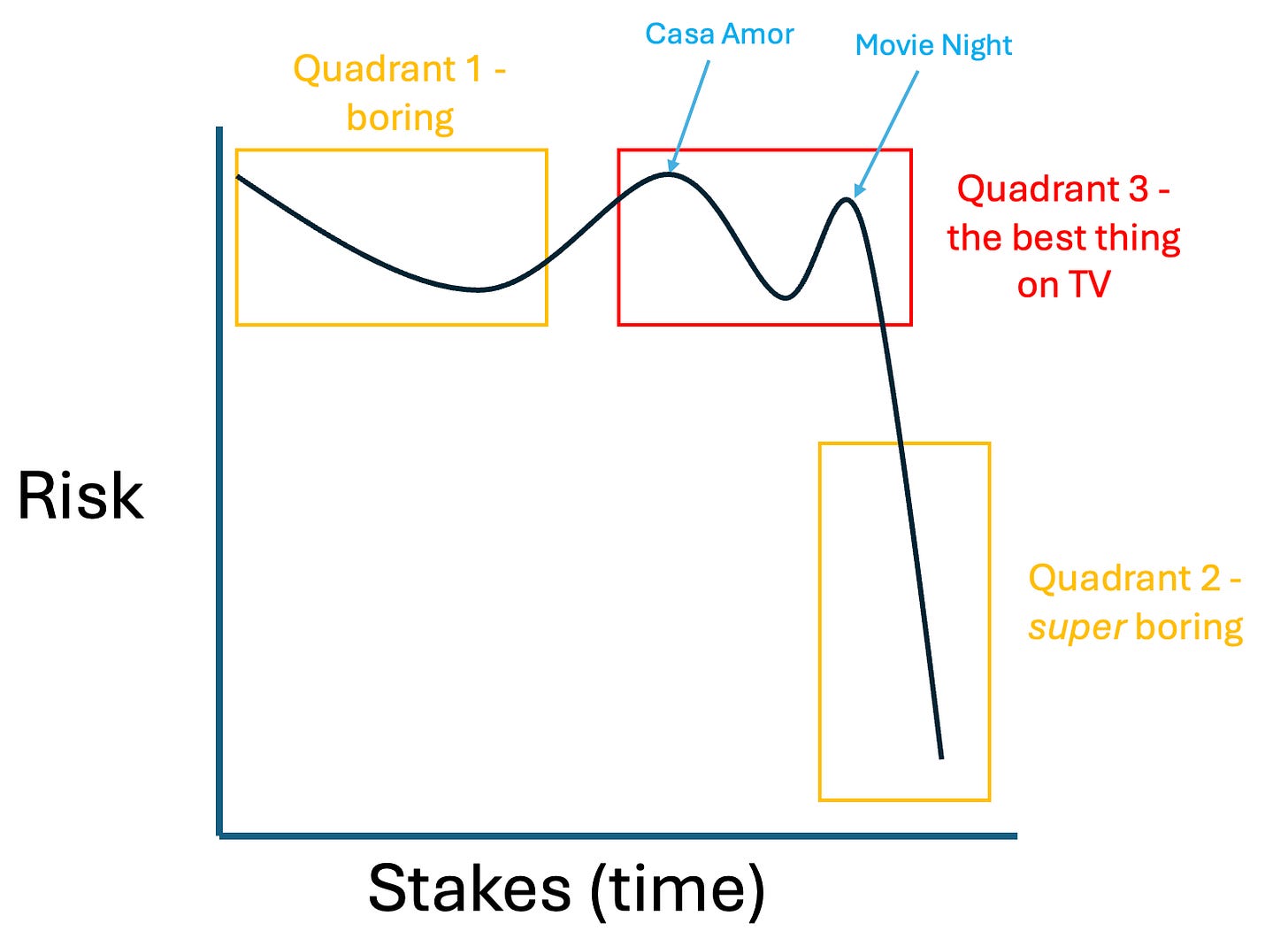

The chart below illustrates this idea. The X-axis represents the stakes - or the degree to which breaking up feels meaningful, translating to higher entertainment value for the viewer. Since the stakes of a breakup are higher for a month-old couple than for a day-old couple, this axis doubles as a proxy for time. The Y-axis, on the other hand, represents the risk that a given couple will break up. In other words, it tracks the likelihood that something will go wrong. This is the primary lever for the producers to manufacture drama.

Quadrant 1 - A lot happening but it doesn’t matter

The top left quadrant is the show’s introductory phase, meant to familiarize us with the contestants and the contestants with each other. You’d think this would be entertaining, but you’d be wrong. A lot is happening, the islanders are sizing each other up, relationships are forming and dissolving in minutes, etc. However, the entertainment value is low because the stakes are low. It doesn’t feel meaningful because there hasn’t been enough time for committed relationships to form or for the viewer to get to know the contestants.

Quadrant 2 - Nothing happens

Love Island differs from other dating shows, like The Bachelorette, in that the ending is the least interesting part. I don’t think I’ve ever actually finished a Love Island season; it’s just not why you watch. The boredom arises from the opposite problem as Quadrant 1 — the stakes are high, but it doesn’t matter because the risk of a breakup has fallen to near zero, and the show loses its raison d’etre.

Quadrant 3 - The purest form of entertainment right into your veins

The best part of the show is when both the stakes and risks reach their peak, which happens around 60% of the way through. The climax comes with two separate events that happen in quick succession - Casa Amor and Movie Night. Both are interesting for their own reasons, but they share real risks for the couples and enough time has passed for it to feel meaningful.

Casa Amor

Casa Amor undoubtedly begins the 5-7 episode streak that is the peak of the show. At a certain point, all contestants of a specific gender, let’s say the men, get sent to a different villa, with an equivalent number of new women. At the same time the original group of women contestants get an equivalent number of new men staying with them at the villa. The contestants stay in their newly assigned villa for 3 days in complete isolation before converging back to a single villa. The “original” contestants get to decide if they want to “bring back” one of the new contestants. I cannot overstate the intensity of the drama this produces. The “new” contestants are hell-bent on getting selected to come back, and the original contestants must decide if they are going to betray their existing couple for someone new. The process by which these decisions are revealed to the viewer is masterfully manicured reality TV gold.

If you want to get a sense of what a Casa Amor reveal looks like, this clip shows a contestant bringing back someone from Casa Amor, despite being in a strong couple beforehand (sorry for the quality).

Movie Night

If you assumed that “whatever happens in Casa Amor, stays in Casa Amor”, you’d be mistaken. Anything scandalous that wasn’t brought up naturally gets revealed during Movie Night.

There’s a phrase I first heard from Alex Danco called “social fog of war”, which describes the necessity of information obscurity to ensure social cohesion. This means limiting common knowledge - or the degree to which others know that others know that others know...and so forth. Scott Aaronson in his essay on common knowledge describes this best:

Whereas, in social contexts, very often you’re managing a delicate epistemic balance where you need certain things to be known, but not known to be known, and so forth—where you need to prevent common knowledge from arising, at least temporarily.

I have an unpublished essay that uses these concepts to explain the disproportionate amount of drama and upset feelings caused by weddings. Normally, people don’t know their exact place in a specific social hierarchy - it is obscured by the social fog of war. But weddings lift the social fog of war by letting everyone know where they stand through determining who gets an invite, who’s in the wedding party, who sits at what table, etc. This moment when the fog lifts cause things to become known that aren’t supposed to be known.

The underlying importance of Movie Night, and hence why it comes after Casa, is to ensure everything that happened at Casa becomes common knowledge. Movie Night encapsulates the delicate epistemic balance that is the social fog of war, and it causes a tremendous amount of chaos. Without Movie Night, “Bro Code” could prevent dramatic information from reaching the women, and vice versa.

II.

There is an interesting dynamic related to authenticity that is pervasive throughout the show. The explicitly stated goal of contestants is to find love, but everyone knows that’s not the real reason. It shouldn’t be a surprise that love-based reality shows have a very poor track record of helping people find love. Considering the contestants know this, we can assume their primary motivation is to become a famous influencer. This also shouldn’t be a surprise, nor is it very interesting by itself. What is interesting is that the ultimate faux pas for a contestant is to reveal that they are just there for clout. Letting their true motivations slip is usually a death knell — the public turns on them (which matters for voting), and the contestants also turn on them (probably because they know the public will).

So, if your objective is to become an influencer, but you need to pretend like that isn’t your objective, what do you do?

The obvious answer is to get the watching public to like you, to become a “fan favourite”, if you will. Ideally you have some combination of “qualities” that are suited to becoming an influencer. One way to improve your chances would be to analyze what’s made successful fan favourites historically and then mimic their traits. While in theory this could work, I don’t think it happens in practice. Strategically acting inauthentically for long periods of time ( seven days a week for weeks on end!) is extremely hard to do. Sure, Jeremy Strong or Daniel Day-Lewis could do it, but we aren’t dealing with professionals. Far from it.

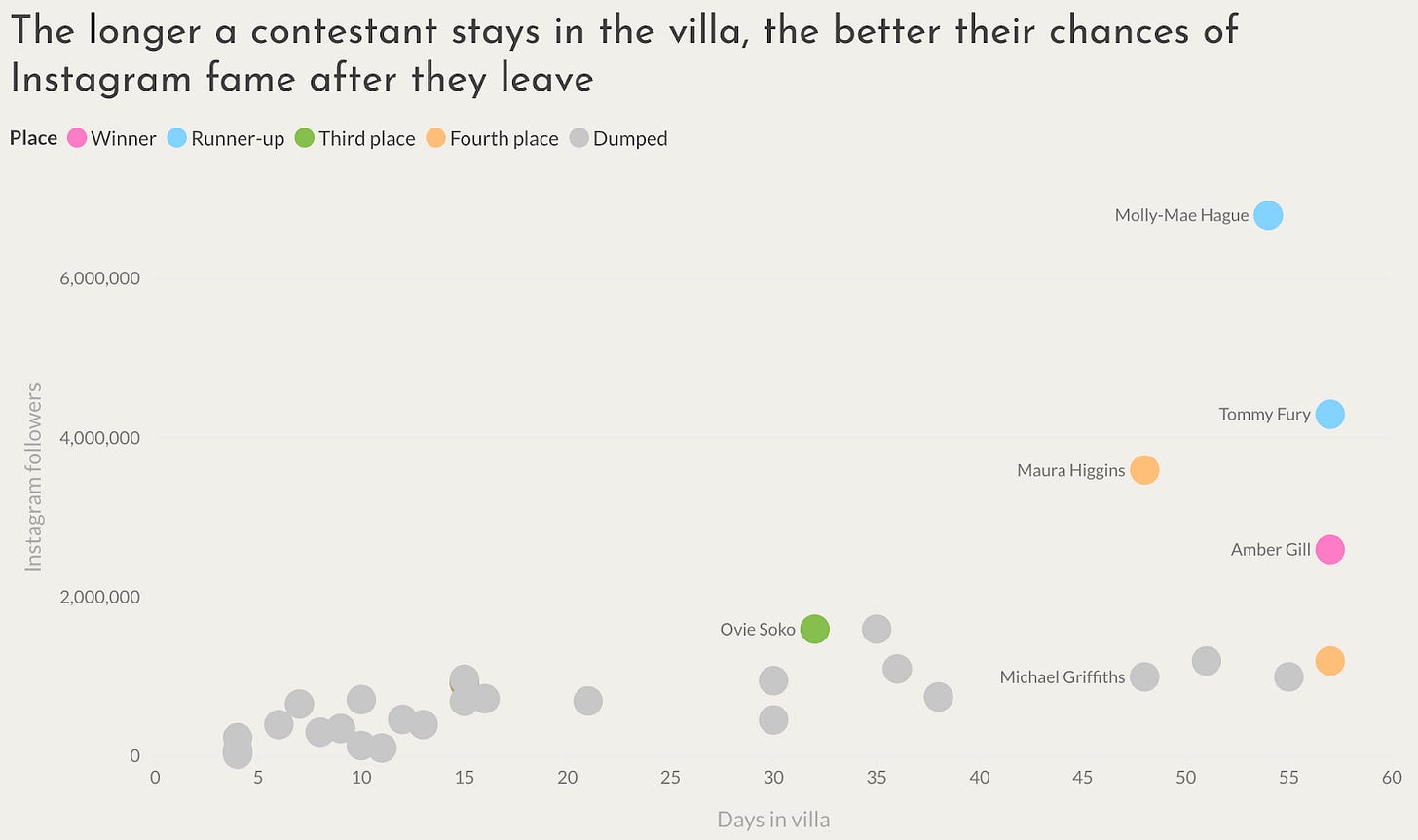

If intentionally changing your personality is too hard, then the only other option is quantity, which means maximizing one’s days on the show. It doesn’t matter how boring you are, the more time you can be in front of the audience, the more Instagram followers you will get. Believe it or not, someone actually has a graph for this:

The astute reader may question the causality — it may not be the quantity that leads to fame, but instead those with influencer “qualities” tend to last longer. This may be partially true, especially for the real talents, but overall it doesn’t change the strategy: it is very hard to become famous from Love Island if you quickly get kicked off Love Island.

To stay on the show, the contestants need to actually play the game: find a couple, convince the other contestants and the public that it’s authentic, and don’t get dumped. This is the hilarious paradox of the authenticity of the contestants. Their implicit motivation is fame, but to achieve this they must maximize their time on the show, which means trying to fall in love. Therefore, it’s reasonable to assume that most contestants are acting authentically!

III.

Usually once per episode I find my mind has drifted off attempting to figure out what weird human quirk makes this enjoyable to watch. Specifically the parts where a happy couple is imploding before my eyes. I don’t think it’s schadenfreude. I don’t feel joy or pleasure when watching the misfortune of contestants, but I am highly entertained. Why?

The most interesting answer to this question is the biological argument. What we are watching is gossip in its purest form, and we are wired to like it.

In 1996, Robin Dunbar argued in Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language, that human language evolved due to an evolutionary need to gossip. The argument goes something like this:

Many mammals live in groups to improve their reproductive odds. The great apes are especially social, managing complex social hierarchies. Large groups have many advantages, but maintaining their cohesion is hard. There needs to be a mechanism that builds trust and regulates cooperation, or else the group fractures. Non-human apes do this through grooming.

The problem with grooming, however, is that it doesn’t scale. Grooming is inherently a one-on-one activity that must be done between nearly all members of the group, meaning time spent grooming grows as group size increases. Since grooming is essential for maintaining social bonds, larger groups must dedicate more time to grooming, cutting directly into their time spent on critical tasks like finding food.

This limitation effectively caps group size, leaving us with a biological trade-off: groups can only grow as large as the time they can reasonably spend grooming. For most primates, this cap seems to be around 20% of their time. This is illustrated through our closest relative, the Chimpanzee. Chimps have a mean group size of 55, and dedicate roughly 20% of their time to grooming.

The average group size for early humans was much higher than 55, about three times, which Dunbar famously put around 150. If humans used social grooming to maintain a group size that big, we would have to spend more than half our time grooming. So we didn’t, says the theory, we started talking instead. And not talking about abstract concepts like gods, we started gossiping about other humans. Since gossiping allowed us to form social connections quicker with more than one person at a time, it expands the group size cap inherent to social grooming, and allowed humans group size to grow.

Much like how reproduction is incentivized by feeling good, gossiping releases significant amounts of oxytocin, which is a hormone that seems to do a lot of childbirth related things but also boosts social bonding, positive emotions, and stress reduction. Our body makes it feel good to talk about others, because maintaining our group size was an important evolutionary trait.

I think this is as good a theory as any for why we like reality shows, especially dating shows. They recreate a small band of humans and use artificial rules to maximize the amount of gossip. You also have no risk of the gossip turning on you — it’s only upside!

IV.

When first trying to come up with a way to conclude this post, I came to the realization that my essay was turning into a Love Island episode — with a drawn out ending where nothing substantial happens. Therefore, I hope you can appreciate me saving you the time and abruptly ending here.