Context Completeness

A better way to evaluate information sources

Whenever we consume information, whether a book, article, or video, there's a familiar echo in our minds: "is this biased?" This question grows louder when the topic is tinged with politics. Similarly, when we hear about information that others consume, we may drop the question entirely and think: "this is undoubtedly biased."

The issue with this framing, though, is that everything is biased, leaving us with a question that always resolves to “yes”. In this essay I want to introduce a different question for you to ask. Instead of evaluating information sources in a binary way (biased or unbiased), I want to suggest using a method called “context completeness.” This method requires you to think about what percentage of the context a specific media source is giving you. For example, a news source with a context completeness ratio of 50% would be giving you half of the relevant information or evidence, while leaving out the other half.

So instead of asking “is this biased”, you should be asking “what is the context completion ratio?” I know, it doesn’t roll off the tongue and it might be the nerdiest thing you have ever heard, but that doesn’t mean it's not helpful.

Despite the veneer of numeracy, context completeness is not a quantitative measure. While I wouldn’t say it's subjective, it's impossible to actually calculate. However, it's still a useful mental framework.

A source with 0% context is making a claim without any evidence at all. It doesn’t necessarily mean the claim is wrong, but there is no way to verify it. Another name for this is entertainment, as it's akin to getting your information from the latest episode of Succession. Sources with 0% context completeness are usually awesome, they’re just not good ways to get new information.

On the other hand, sources with 100% context completeness are rare, and even if you do find one, you probably won’t like it. Having 100% context means 1) there is a mountain of evidence and information, likely more than you have time for, and 2) it's going to be extremely boring. Academic papers are probably the only sources that get close to 100% context. The ideal context completeness for something like news is probably between 70% and 80%. This gives the source enough context to show an accurate picture, but not so much that its entertainment value sinks low enough to be unreadable.

The entertainment-context dichotomy is a good way to spot a source with low context completeness. The more entertaining, usually the less context is being provided. This isn’t always true, but it's a decent proxy. Additionally, if you find your-self nodding along in agreement (or disagreement), or getting “fired up” about what you are reading or watching, odds are it has low context completeness.

On the flip side, two indications that a source has high context completeness are:

They are considered unbiased by nearly everyone (this is rare)

They are considered liberal by conservatives, and conservative by liberals (it doesn’t have to be political groups, just anytime two opposing “sides” both say a source is favoring the other side)

Someone may have their hand up at this point with the question “but what if the context that is being provided is fake or made up?” It's a good question, but my response would be: first, fake context is not context, so 0%. Second, you may be surprised to know that information sources very rarely make up context, they just choose it selectively. This is the assumption that context completeness is based on.

Let me say it again so it's crystal clear for those in the back: most media outlets, political YouTube shows, and even bloggers, don’t usually outright invent facts. Instead, they form conclusions based on selectively chosen evidence. Scott Alexander has an article discussing this here and here. Let’s look at two examples from the article and apply a context completeness ratio to them.

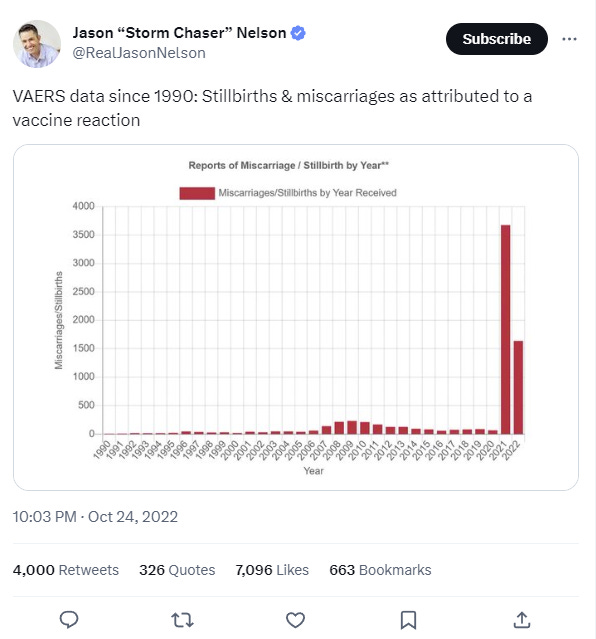

Where better to start than with InfoWars, which ran an October 2022 headline: “New Vaccine Data Shows Alarming Number Of Stillbirths And Miscarriages Caused By Covid Shot”, citing this chart:

At first glance, this chart looks pretty worrying. Our first instinct may be to question if the data is made up or not, but it's not, it comes from VAERS, which is co-managed by the CDC and FDA. Infowars took this real information and logically concluded that the 4,000% increase in miscarriages in 2021 was due to the COVID vaccine.

Although, as you may have surmised, they omitted vital context surrounding the data in the chart, such as the fact that the data relies on women voluntarily self-reporting. If Infowars had had a higher context completeness ratio, they would have added:

Since the VAERS data looks at a small slice of total miscarriages - women who received a vaccine in the last year - any increase in the number of women who received a vaccine in the last year would increase the VAERS numbers, and a lot more women got a vaccine in 2021 than in 2020.

Remember that it's self-reported, women in normal years don’t have vaccines on their mind, and likely don’t report their miscarriages to VAERS after getting one. In 2021 and 2022, vaccines were on everyone's mind, leading to more people remembering to report. The same thing happened in 2008-2010 with the HPV vaccine, which eventually dropped back down to normal levels.

There is no verification by VAERS that the reports are true or not. I could go right now and report a miscarriage to VAERS.

And this is just context for the chart itself, there are a ton of studies about this exact subject with different conclusions that could have been referenced.

Note that I am not attacking InfoWars conclusion directly, instead I am focusing on the missing context of their conclusion. But it is important to call out that they didn’t lie. They may have pushed a conclusion with a context completeness ratio of less than 10%, but the numbers in the story were not fabricated. Now, did they nefariously withhold context to fit their narrative? Are they just really really dumb? Probably both, but they didn’t technically lie.

Let’s look at one more example, but this time from the left.

The Washington Post had a headline from a few years ago titled Scott Walker’s yellow politics, where they take issue with the (then) governor of Wisconsin, Scott Walker, who had a proposal to make welfare benefits dependent on a drug test. The author of this story goes into why this is a bad idea because welfare recipients barely use drugs at all! To back this up, she cites a study: “In Tennessee, more than 16,000 applicants for public assistance were screened for drug use under a new state law; exactly 37 tested positive, or about 0.2 percent.” The author implies that since welfare recipients use drugs so seldomly, there is no need to force drug tests for benefits. 16,000 is a lot of people too, so small sample size certainly isn’t an issue.

Again, some key context was left out. It would have been nice to know:

“Screened for drug use” didn’t mean a drug test, it meant asking welfare recipients a Yes/No question on if they took drugs or not. It was self-reported.

Depending on how you calculate it, the percent of US drug users across the entire population is 5-10%. Since this study indicates 0.2% of welfare recipients take drugs, that’s like 98% less than the general population.

However, just like InfoWars example, WaPo didn’t lie. This was a real study, with real numbers, they just left out the fact that the government asking people if they took drugs obviously led to a low rate of affirmations.

Aside from putting in this obviously flawed Tennessee study, the author does include additional context and studies about the welfare drug-test debate. Despite failing to include any studies that point to drug use potentially being higher among the poor, this article is probably closer to 50% context completeness. Not bad, but not great.

Again, I am not taking an issue with the author's overall point, just with the amount of context she decided to include.

I also want to call out that these articles were not cherry picked - you can go to the website of any news outlet or blogger and choose virtually any article, each one will have left out some degree of context.

Conclusion

As you can see from these examples, both these articles would qualify as biased, which doesn’t help us at all. If everyone is biased then no one is biased. The more effective question, that places an information source on a spectrum rather than a transistor, is “what's my context completeness ratio?” We must understand that information can be selected and presented in a myriad of ways, and rarely is it comprehensive or fully contextualized. Context completeness equips us to evaluate the information we consume not in unary terms of biases but by allowing us to appreciate the degree of the context provided.

Media sources spanning from Infowars to the Washington Post present true information but remove varying degrees of context to fit their narrative. This is why “banning misinformation” is problematic. Would either of the aforementioned articles be misinformation? They both stated true facts, they just withheld context, is that misinformation? Perhaps a better way to define misinformation would be something like “presenting oneself as news but having less than 5% context.”

In fact, we used to legally enforce high context completeness on broadcasters from 1949 to 1987, it was called the fairness doctrine. This is probably unrealistic in the information age, but the concept is intriguing nonetheless.