Book Review: A People's Tragedy

A comprehensive summary of the Russian Revolution

"Sometimes, history needs a push" - Vladimir Lenin

The above quote touches on a long debated historical question: can history be explained by the outsized impact of “great” people or heroes? Or do bottom-up human and social dynamics govern the course of events?

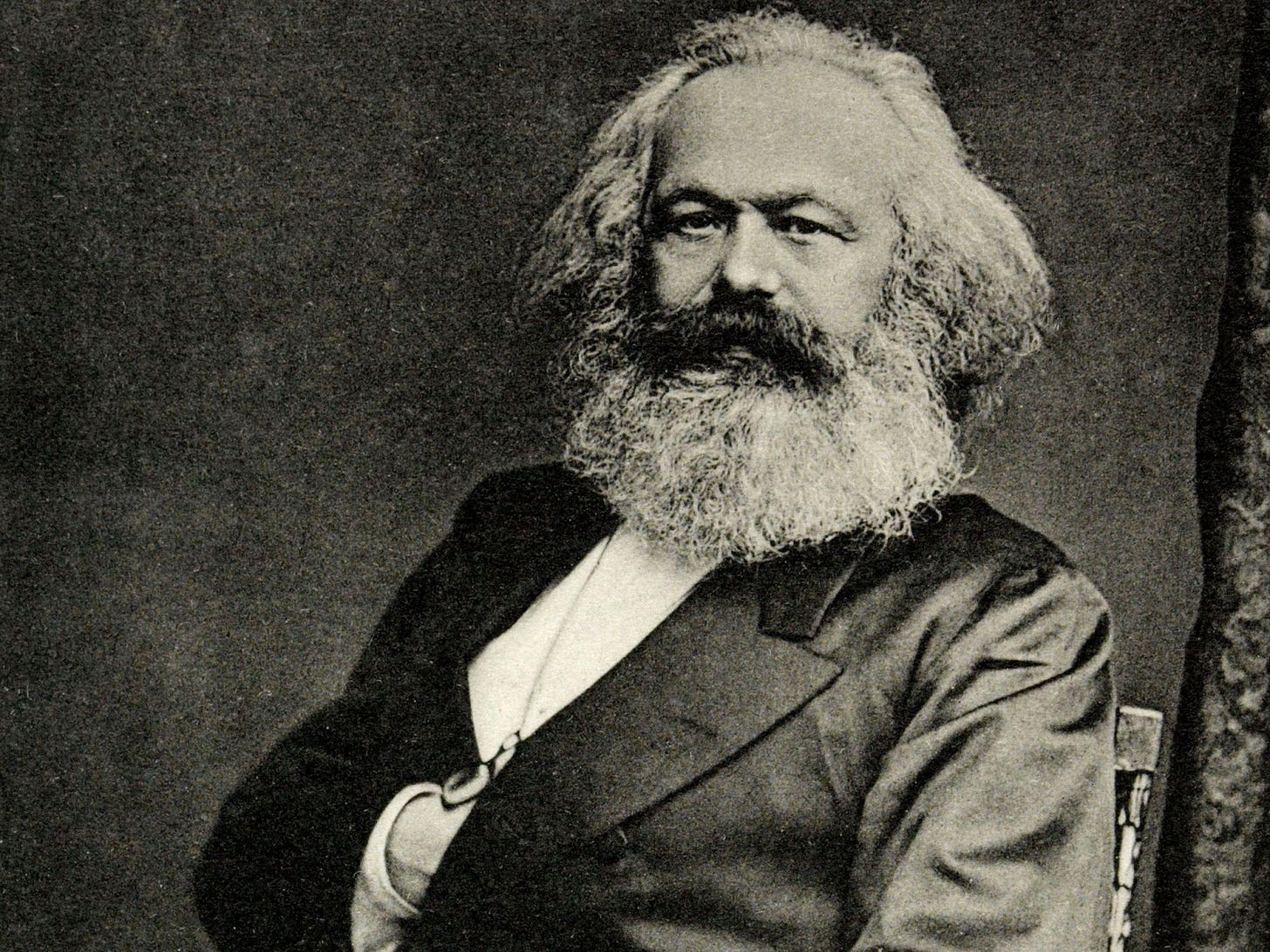

Leo Tolstoy had a strong opinion on the matter, as a major theme in War and Peace is about the limits of leadership and an outright rejection of the great man theory. Karl Marx is known for his theory of history called historical materialism, which also rejects the great man theory and instead explains history through changes in class and labor.

I use Tolstoy and Marx as examples because of their proximity to this story, but also because the events that occurred in Russia up until 1917 are easily explained through their theories. It was only a matter of time before the societal changes happening at the beginning of the 20th century were going to bring about an end to the tsar.

However, what happened in November of 1917 can only be described as the great man theory at work. Our world would look a lot different if Lenin was not around to give history a “push”.

This essay will be a book review of A People’s Tragedy by Orlando Figes, one of the most coveted books on the Russian Revolution. As Figes apologizes in the introduction of the book, I will do the same here: I am sorry for the length.

Let’s dive in.

Part I: The Decline of the Romanovs

The Romanovs were the ruling family of the Russian Empire for more than 300 years (1613 to 1917). The family had a great cast of characters that you may be familiar with: Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, and Ivan the Terrible. The word for emperor in Russia is tsar (or tsarina). In Gothic, it would look like kaiser, but its origin is Latin, and would look like caesar.

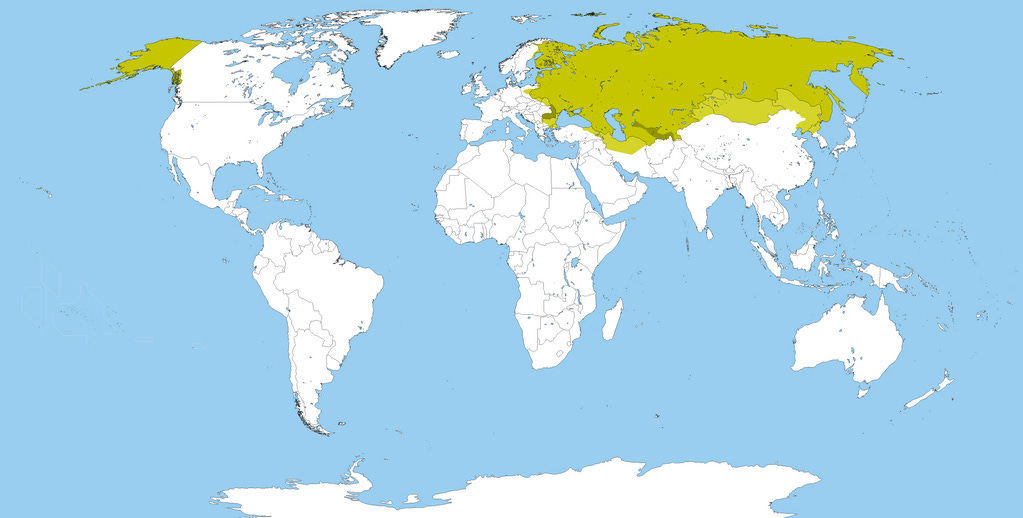

Over their three century long rule, the Romanovs had some highly effective conquerors who grew the Russian Empire significantly. By 1895, they had conquered their way to the third largest empire of all time (beaten out only by the Mongols and the British), accounting for 17% of the Earths land area. This included 16 modern-day nations including Russia, Poland, Finland, Ukraine, Mongolia, and more.

However, after many years of prosperity, the effectiveness of the tsarist regime began to falter.

The story begins with the Russian famine of 1891. Caused by a series of unfortunate weather events and government mismanagement, the famine resulted in 375,000 to 400,000 deaths. Figes writes about the famine:

In short, the whole of society had been politicized and radicalized as a result of the famine crisis. The conflict between the population and the regime had been set in motion and there was now no turning back. In the words of Lydia Dan, the famine had been a vital landmark in the history of the revolution because it had shown to the youth of her generation 'that the Russian system was completely bankrupt. It felt as though Russia was on the brink of something.’

The tsar at this time was Alexander III, a conservative by tsarist standards, he opposed any reform that would threaten his autocratic rule. He was effective at maintaining order but died in 1894, which suddenly made his 26-year-old son Nicholas II the new tsar of Russia.

Nicholas gets a lot of attention in this story because he was a below-average leader during an extraordinary time. Although he was also a deeply tragic figure. He loved his family deeply and did not want the throne, but felt he had to maintain his ancestors 300-year streak of unadulterated autocratic rule.

Revolution and War

One of Nicholas’ first big blunders was the 1904 Russo-Japanese War, caused by rival ambitions in Manchuria. This war is historically significant because it was one of the first conflicts with modern weapons. Artillery cannons begin to look closer to something you would see today, as opposed to a cannon you would see in the American Revolutionary War or the Napoleonic Wars. Additionally, machine guns and turrets became widely used.

However, most of this modern weaponry was being used by the Japanese.

The biggest problem was the sheer incompetence of the [Russian] High Command, which stuck rigidly to the military doctrines of the nineteenth century and wasted thousands of Russian lives by ordering hopeless bayonet charges against well entrenched artillery positions.

The war can be summed up in a mental image of Russian cavalry charging on Japanese artillery. If you also consider that the war was 6,000 miles away from the Russian capital, being supplied by faulty railroads, they never had much of a chance. The numbers vary, but roughly 60,000 Russian soldiers died in the conflict.

In January of 1905, mass demonstrations began in the Russian capital of St. Petersburg sparked by the trifecta of humiliation of the war with Japan, hunger, and peasant exploitation. To quell the demonstrators, state police opened fire on the crowd and killed hundreds of civilians. The day became known as “Bloody Friday''. In June of the same year, peasants also began rioting by seizing land and tools in protest of the bureaucracy imposed on them. Throughout the year, the tsarist regime executed 15,000 people and exiled 45,000, which didn’t make the situation better.

The revolution had been truly born, and it had been born in the very core, in the very bowels of the people. In that one vital moment the popular myth of a Good Tsar which had sustained the regime through the centuries was suddenly destroyed.

These events collectively made up the Revolution of 1905, which culminated in the October Manifesto, a document begrudgingly issued by Nicholas that promised basic civil rights and an elected parliament.

This is a key part of the story. So far, the events look like what happened in, say, the United Kingdom, where the people slowly chipped away at the rights of the monarch until they ended up with a system that was democratic. But did the October Manifesto and subsequent constitution go far enough?

This was, in truth, the main dilemma that the liberals faced after the October Manifesto - whether to support or oppose the government. So far the revolution had been a broad assault by the whole nation united against the autocracy. But now the Manifesto held out the prospect of a new constitutional order in which both monarchy and society might — just might — develop along European lines.

The new government body, called the Duma, ended up not having much power at all, which set Russia up for another revolution 12 years later.

Revisionists look at this part of the story very closely. If Nicholas had ceded more power to the Duma, there may have not been the need for a revolution. Additionally, a parliamentary government may have avoided entering WWI, which would have changed the entire history of the 20th century.

It's also worth looking at why the 1905 Revolution failed. Why was the tsar able to remain in power? First, the various opponents failed to unify politically or tactically. The striking workers, rebelling peasants, and armed service mutineers didn't coordinate their actions at all. Second, the military largely remained faithful to the tsar. History shows that it's hard to have a successful internal revolt without the support of the military.

Lastly, there was no aligned vision on what the replacement government should have been. On one hand, it's easy to blame Nicholas for not ceding enough power to the Duma, but on the other you could blame the revolutionaries for not proposing a comprehensive replacement. There was a wedge created within the opposition around the October Manifesto. The liberal socialists felt it didn’t go far enough and wanted to continue the revolution, whereas the moderates thought it was a good first step towards political reform.

But in large, the people were blinded by the hopium.

Most of the Duma members shared [the] faith that Russia had at last won its House of Commons' and would now move towards joining the club of Western liberal parliamentary states. The time for tyrants was passing. Tomorrow belonged to the people. This was the Duma of National Hopes.

Nonetheless, the leader of the Duma was assassinated in September of 1911, wiping out the dreams of traditional political reform. We will never know what could have been if this had been successful, but it’s sure entertaining to theorize.

The Great War

Fast forward to June 28th 1914 and there is another assassination that’s important to this story. A radical Serbian named Gavrilo Princip shot the heir to the Austro-Hungarian empire, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, as he is visiting Sarajevo. This led Austria-Hungary to declare war on Serbia, which caused the two stronger allies of each country, Germany and Russia, to declare war on each other. The most cited cause of World War I was the web of military alliances across Europe. While this was true, examining Russian motives a little closer can give us a better picture as to why this struggling nation decided to go to war.

One way to view Russian history is to see a country deeply confused about its identity. It so badly wants to be European (specifically, German) but it feels like it can’t shake its Asian-ness. Russia at this time has what I can best describe as Stockholm Syndrome in regard to German culture. Figes focuses on this a lot:

This fear of Germany stemmed in part from the Russians' cultural insecurity - the feeling that they were living on the edge of a backward, semi-Asian society and that everything modern and progressive came to it from the West. There was, as Dominic Lieven has put it, 'an instinctive sense that Germanic arrogance towards the Slavs entailed an implicit denial of the Russian people's own dignity and of their equality with the other leading races of Europe.’

It’s relevant to note that Germany was the cultural and scientific epicenter of Europe (and hence the world) at the time. The unification led by Otto von Bismark in 1871 set Germany up for 40+ years of dynamic success. Many of the greatest minds of the day were either from or lived in Germany, including philosophers like Marx, Hegel, and Nietzsche, along with scientists such as Einstein and Planck.

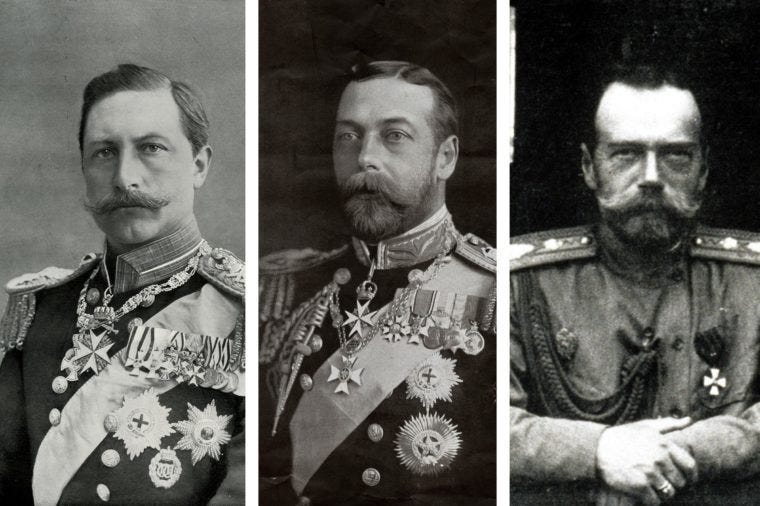

But let’s not forget that Russia’s decision to enter the war was ultimately on the shoulders of one man - Nicholas - who had personal motives outside of alliances and cultural insecurities. For starters, Nicholas was cousins with the leader of Germany, Wilhelm II (they were both also cousins of George V of England).

On one hand, I long for the day we can get back to the world of great mustaches that was the late 1800s. But I digress.

Nicholas was likely making his decision to enter the war based on what was best for preserving his power. Figes believes that instead of looking at the war opportunistically, he was choosing between the lesser of two bad options.

This placed Nicholas in an impossible situation. If he went to war, he ran the risk of defeat and a social revolution; but if he didn't, there might equally be a sudden uprising of patriotic feeling against him which could also result in a complete loss of political control.

Whatever the true reasons for his decision, he mobilized the military which prompted Germany to declare war against Russia in August 1914.

Tensions had been high for a long time in Europe, especially with Germany. The Germans were squeezed in between two powers that they were not on the friendliest terms with: France and Russia. For this reason, Germany devised a plan decades before called the Schlieffen plan, to defeat both France and Russia if it ever came to it. The plan was based on the fact that Russia was strong but extremely slow. If Germany could quickly invade France and knock them out within a few weeks, then they could move their undivided focus to Russia, ensuring they don’t have to sustain a two-front war.

As described in the Schlieffen plan, the Russian military has historically been characterized as strong but slow. This characterization is largely correct; however, Russia’s problems in the first world war went much deeper than just slowness. The Russians got completely destroyed in World War I. They hadn’t learned as much as they should have from the war with Japan, such as focusing too much on cavalry (yes, horses). Their supply lines were non-existent and hence they were unable to arm, cloth, or feed their men.

Without artillery or supplies of ammunition, they held out as best they could, suffering heavy losses. Many men fought with nothing but bayonets fixed to their empty rifles.

Additionally, most of the Russian army was made up of peasants being led by landowners. These were the same landowners who the peasants had been actively rebelling against for the last ten years. The social issues of the country carried over to the army, which preserved the feudal customs such as soldiers addressing officers by their honorary titles and constantly cleaning their boots. This led to a slew of morale issues, including constant mutinies and desertions.

The sole redeeming facet of the Russian military effort in World War I was their general Aleksei Brusilov, who was unbelievably able to deliver some decisive victories against the Austro-Hungarians. Despite being a pretty optimistic guy, Brusilov eventually realized the effort was hopeless.

Brusilov had shown that under competent commanders the imperial army was still capable of military success. Had it not been undermined by Stavka, his offensive might have served as the springboard for the restoration of the army's morale, perhaps even one day leading towards its eventual victory. But it is doubtful whether even this would have been enough to save the tsarist regime, such was the extent of the political crisis in the country at large. In any case, with the failure of the offensive it now became clearer than ever, even to a monarchist like Brusilov, that, in his own words, Russia could not win the war with its present system of government. Victory would not stop the revolution; but only a revolution could help bring about victory.

A fun revisionist hypothetical to play with is if the Russians were even half-way competent, and Brusilov had been given what he needed, there is a strong chance the US would never have needed to enter the war.

The last relevant event that occurred before 1917 was the death of Rasputin. If you’re wondering why I haven’t brought up Rasputin yet, it’s because I don’t feel like he matters that much to the story. I look at him more like a symptom than a cause.

By the time we get to 1917, any trust remaining with the monarchy was hanging by a thread. But as the last breaths of power left the Romanov Dynasty, a new ideology was rising in the west.

Part II: The Rise of Communism

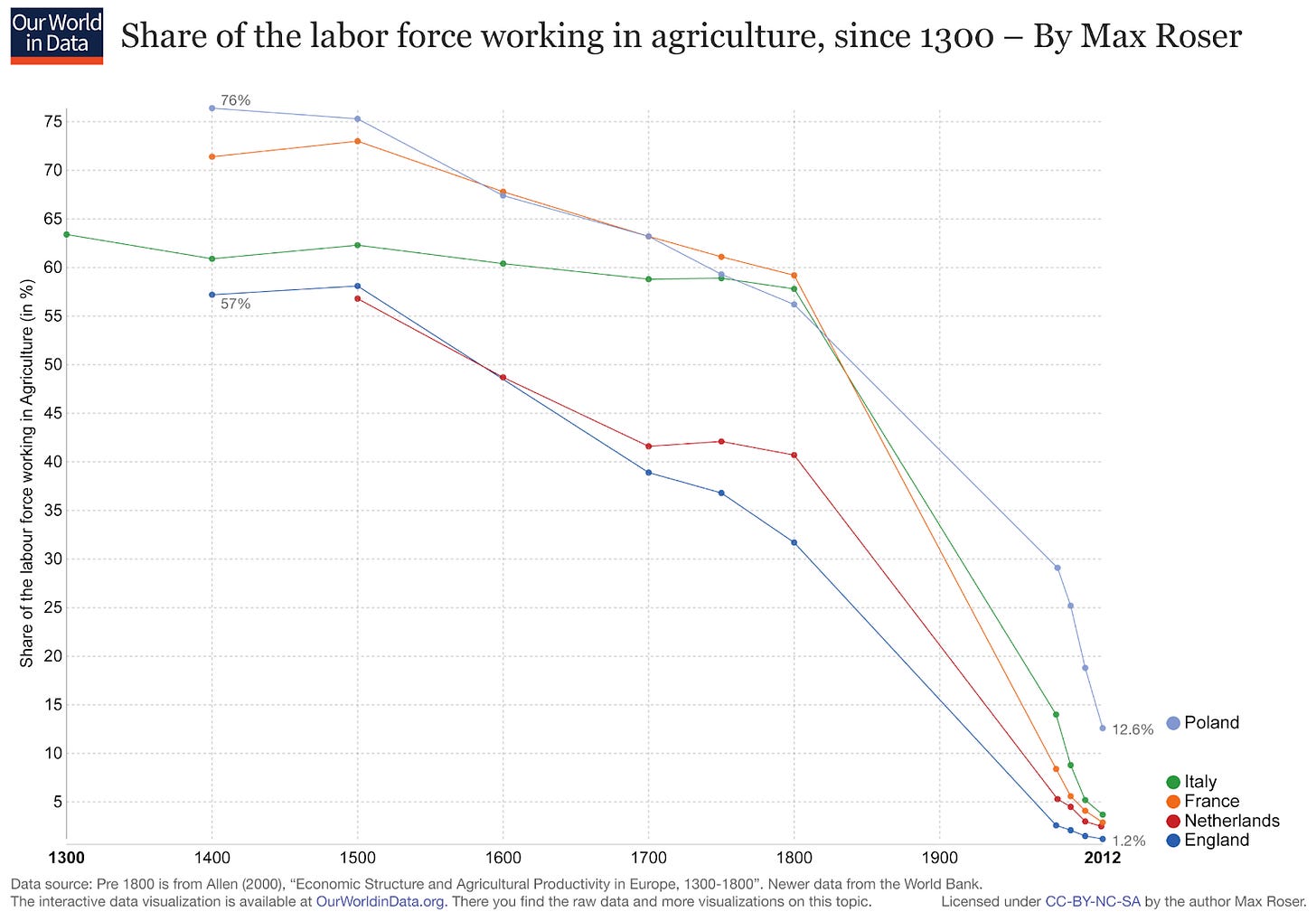

Fueled by the Industrial Revolution, life began to change rapidly in the 1800s. Young people left their family’s farm to move to the city and work in a factory. The below chart shows the percentage of the labor force working in agriculture over time (note: Russia isn’t on the chart, but it would most closely resemble Poland since it was apart of the Russian Empire).

The tsarist regime's ultimate failure was its inability to handle the consequences of modernization. This chart is what is meant by modernization.

Capitalism became much more relevant for societies with factories rather than farms. In purely agrarian societies, farmers are mostly independent and use their own land and labor to feed themselves and their families. Farmers (that weren’t serfs) owned the means of production, but workers in the factory did not. The mass migration of people to cities, with no labor regulations to speak of, led to some awful working conditions and a tremendous amount of inequality. The majority of people in Russia at this time were getting the worst that capitalism had to offer, and they were pissed about it. However, bad working conditions and inequality alone are not usually enough to start a revolution. People need something to rally behind.

The question then turns to the most important idea in this story: communism. The origins of communism trace back to Karl Marx’s magnum opus, The Communist Manifesto, written in 1848 as a critique of the poor conditions across capitalist Europe.

But Marx was a German living in London, so why was Russia the country whose name will forever be associated with his greatest idea?

Literacy and Ideas

In 1800, only 5% of the Russian population could read. Compare this to 50% in England and 30% in France. Although by 1897 the Russian literacy rate had grown to 21%, and by 1917 it had reached 43%.

Figes spends a lot of time on this:

The link between literacy and revolutions is a well-known historical phenomenon. The three great revolutions of modern European history, the English, the French, and the Russian all took place in societies where the rate of literacy was approaching 50 per cent… Ironically, in its belated efforts to educate the common people, the tsarist regime was helping to dig its own grave.

Despite spending time and money educating the populace, the tsars ironically also heavily censored the reading material allowed inside the country. We often associate communists as the ones restricting ideas, but this censorship model was always how Russia operated.

When the censors read the revolutionary rhetoric of Marx, which told the workers to unite and overthrow their capitalist overlords, they surely decided to censor it, right?

Wrong. In one of those amazing little quirks of history, for some reason the censors decided NOT to block The Communist Manifesto because they thought no one would understand it. Of course, in a land devoid of ideas with an exploited population, something as fiery as Marx spread like wildfire. Figes insinuates that Marxism took hold in Russia due to the lack of any competing and contradictory ideas.

The censor forbade all political expression, so that when ideas were introduced there they easily assumed the status of holy dogma, a panacea for all the world's ills, beyond questioning or indeed the need to test them in real life. One European intellectual fashion would spread through St Petersburg: Hegelianism in the 1840s, Darwinism in the 1860s, Marxism in the 1890s and each was viewed in turn as a final truth.

This seems important. If your society only gets a few ideas, does that make people more likely to latch on to the few ideas they do get? Perhaps.

Either way, Marx’s ideas took hold in Russia with the vigor of religion.

Many people have argued that Marxism acted like a religion, at least in its popular form. But workers believed with the utmost seriousness that the teachings of Marx were a science, on a par with the natural sciences; and to claim that their belief was really nothing more than a form of religious faith is unfair to them. There was, however, an obvious dogmatism in the outlook of many such workers, which could easily be mistaken for religious zealotry… This dogmatism had much to do with the relative scarcity of alternative political ideas, which might at least have caused the workers to regard the Marxist doctrine with a little more reserve and skepticism.

But Figes goes into a final reason:

When people learn as adults what children are normally taught in schools, they often find it difficult to progress beyond the simplest abstract ideas. These tend to lodge deep in their minds, making them resistant to the subsequent absorption of knowledge on a more sophisticated level. They see the world in black-and-white terms because their narrow learning obscures any other coloration. Marxism had much the same effect on workers. It gave them a simple solution to the problems of 'capitalism' and backwardness without requiring they think independently.

Does becoming literate and/or educated as an adult cause you to become “resistant to the subsequent absorption of knowledge on a more sophisticated level”? If that’s true it would seem pretty significant.

To briefly summarize, here are the proposed reasons for why Russia was the tinderbox for a Marxist revolution:

Brutal working conditions and inequality for factory workers in the cities

The population was rapidly becoming literate

The censors forbade most ideas, preventing proper discourse about the ideas that got through

#2 and #3 uniquely combined to cause newly educated adults to become irrational zealots

I think I buy this argument. Russia had a tremendous scarcity of ideas, the population was primed with earth-shattering theories like Darwinism, they’re getting the worst that capitalism had to offer, and they got presented with a theory that promised to solve their material needs. Marxism became a simple solution for a complex set of problems broadly labeled as capitalism.

The February Revolution

Getting back to our story, riots broke out on March 8th 1917, to protest the food rationing imposed as a wartime necessity. 250,000 men and women took to the streets to express their dissatisfaction with the food shortages, the war, and autocracy.

(If you're confused by “The February Revolution” being in March it's because the Russians at this time used a Julian calendar. We use a Gregorian calendar, which means it took place in March.)

One key difference between this protest and the one in 1905 is that the soldiers joined the side of the protesters.

The soldiers, by contrast, were seen as 'ours' - peasants and workers in uniforms - and it was hoped that, if they were ordered to use force against the crowds, they would be as likely to come over to the peoples side. Once it became clear that this was so - from the soldiers' hesitation to disperse the demonstrators, from the expressions on the soldiers' faces, and from the odd wink by a soldier to the crowd - the initiative passed to the people's side. It was a crucial psychological moment in the revolution.

The February Revolution was a protest against the monarchy, and after decades of trying it finally worked. On March 15th, 1917, Nicholas II anticlimactically abdicated the throne, ending 304 years of Romanov rule. The ease with which the tsar was overthrown was representative of how much his power had declined. The current parliamentary leaders in the Duma then formed the Provisional Government, which was to be democratic.

It is important to say, though, that the February Revolution was not the communist revolution. Within the Provisional Government there were a handful of left-wing parties vying for power, one of which happened to be the Bolsheviks, and on April 16th, their leader returned to St Petersburg.

Vladimir Lenin was born in 1870 to an upper middle-class family. Radicalized by his brother’s execution in 1887, he began leading various socialist groups in and out of Russia. He was exiled many times and prior to 1917 he was living in Switzerland waiting for his moment to return.

The February Revolution was exactly what Lenin was waiting for: an opportunity to implement his reforms. It's important to note that this wasn’t just an opportune time for him, but also for the Germans. The German’s saw Lenin’s return as beneficial for their war efforts since Lenin and the Bolsheviks publicly promised to pull out of World War I. So, in what is another great historical quirk, the Germans help facilitate Lenin's return to St. Petersburg.

But by the time Lenin arrives in Russia he was practically a stranger. Aside from a brief stay in 1906, he had spent the previous seventeen years exiled abroad. Virtually none of the workers chanting his name upon his arrival even knew what he looked like. “I know nothing of Russia”, Lenin once said to a friend. Yet it didn’t matter, Lenin had complete domination over the Bolshevik party.

No other political party had ever been so closely tied to the personality of a single man. Lenin was the first modern party leader to achieve the status of a god: Stalin, Mussolini, Hitler and Mao Zedong were all his successors in this sense. Being a Bolshevik had come to imply an oath of allegiance to Lenin as both the leader and the 'teacher' of the party.

As Lenin was leading the Bolsheviks, another party competing for power in the new government were the Mensheviks. In general, the Mensheviks were not as radical, and felt a more gradual approach to Marxism was the best way forward.

The Mensheviks were democrats by instinct, and their actions as revolutionaries were always held back by the moral scruples which this entailed. This was not true of the Bolsheviks. They were simpler and younger men, doers rather than thinkers. They were attracted by Lenin's discipline and firm leadership of the party, by his simple slogans, and by his belief in immediate action to bring down the tsarist regime rather than waiting, as the Mensheviks advised, for it to be eroded by the development of capitalism. This, above all, was what Lenin offered them: the idea that something could be done.

The further you go on a political spectrum, the simpler the message gets. This is true today as much as it was with the Bolshevik radicals in Russia. On the other hand, the moderate Menshevik’s message required nuance, something that was greatly lacking in Russia in 1917. For example, here was how they wanted to approach socialism:

Both the Mensheviks and the SR adhered rigidly to the belief that in a backward peasant country such as Russia there would have to be a 'bourgeois revolution' (meaning a long period of capitalism and democracy) before Russian society, and the working class in particular, would be sufficiently advanced for the transition to a socialist order.

Too nuanced god damnit.

The Rise of the Bolsheviks

Lest we forget, Russia was still fighting in World War I, and the new Provisional Government has decided to initiate a new offensive against the Austro-Hungarians. Historians see this as the key mistake that ultimately led to the downfall of the new government. The leaders gambled everything on this offensive hoping the people might rally behind them in a national defense of democracy. It's not clear to me why they thought the war would go any better than it had under the tsar - the soldiers were still under-supplied and poorly motivated after spending three years fighting.

But we already know who wanted to end the war: the Bolsheviks.

As Brusilov saw it, the soldiers were so obsessed with the idea of peace that they would have been prepared to support the Tsar himself, so long as he promised to bring the war to an end. This alone, Brusilov claimed, rather than the belief in some abstract 'socialism', explained their attraction to the Bolsheviks. The mass of the soldiers were simple peasants, they wanted land and freedom, and they began to call this Bolshevism' because only that party promised peace.

Additionally:

The soldiers wanted only one thing - peace, so that they could go home, rob the landowners, and live freely without paying any taxes or recognizing any authority. The soldiers veered towards Bolshevism because they believed that this was its programme. They did not have the slightest understanding of what either Communism, or the International or the division into workers and peasants, actually meant, but they imagined themselves at home living without laws or landowners. This anarchistic freedom is what they called Bolshevism.

I really want to drive this point home. It's easy to look at the parties vying for power after the fall of the tsar, and think that the people of Russia were rationally debating the pros and cons of who they wanted to support and why. This is entirely the wrong way to think about it. People complain about the average voter in the US today - but more than half of the population of Russia at that time couldn’t even read.

Here is Figes again, writing about a Menshevik speaking to some soldiers:

Sometime during March a Menshevik deputy of the Moscow Soviet went to agitate at a regimental meeting. He spoke of the need for peace, of the need for all the land to be given to the peasants, and of the advantages of a republic over monarchy. The soldiers cheered loudly in agreement, and one of them called out, 'we want to elect you as Tsar', whereupon the other soldiers burst into applause. ‘I refused the Romanov crown', recalled the Menshevik, 'and went away with a heavy feeling of how easy it would be for any adventurer or demagogue to become the master of this simple and naive people.'

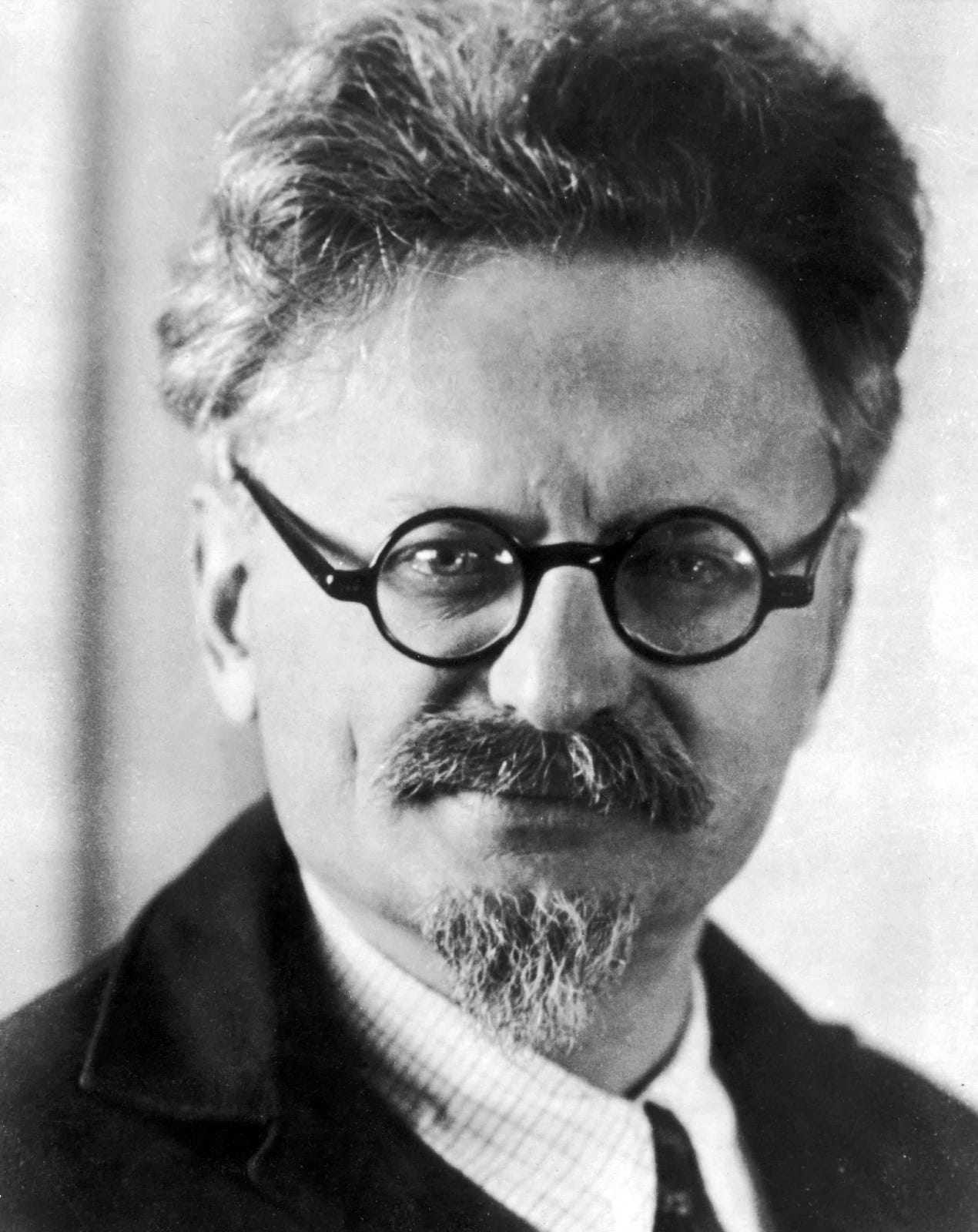

Come July, the failed offensive causes violent anti-war protests to break out in the streets of St. Petersburg, in what is called the July Days. The Provisional Government (correctly) blamed the Bolsheviks for fueling the anti-war sentiments. This caused Lenin to flee, feeling that the entire Bolshevik cause had failed. 800 members of the party ended up behind bars, including one Leon Trotsky.

Trotsky joined the Bolsheviks only a few months before, in what I can only imagine was the 1917 Russian version of Lebron James’ “The Decision”. Trotsky was the most well known revolutionary in the country and a master orator. While Lenin continued to act as the grand strategist, Trotsky became the face of public representation.

Come October, Lenin was beginning to believe that the only way for the Bolsheviks to succeed was to take power by force. This was a hot take among the Bolshevik leadership - many believed they should take over through democratic means: winning seats to get a majority within the Provisional Government. Yet Lenin pushes back:

‘We must not be deceived by the election figures: elections prove nothing... The majority of the people are on our side.’ Reminding his comrades of Marx's dictum that 'insurrection is an art’, Lenin had concluded that ‘it would be naive to wait for a "formal" majority for the Bolsheviks. No revolution ever waits for that... History will not forgive us if we do not assume power now.’

This is Lenin at his absolute best, and an event that demonstrates the decisive effect of a single individual on the course of history. If Lenin had not been around to lead the party during these few weeks, the chance for a coup would have come and gone.

On November 7th, 1917 the Bolsheviks stormed the scantily defended Winter Palace, and took control of the government.

The Great October Socialist Revolution, as it came to be called in Soviet mythology, was in reality such a small-scale event, being in effect no more than a military coup, that it passed unnoticed by the vast majority of the inhabitants of Petrograd. Theatres, restaurants, and tram cars functioned much as normal while the Bolsheviks came to power. The whole insurrection could have been completed in six hours, had it not been for the ludicrous incompetence of the insurgents themselves, which made it take an extra fifteen.

The truth was, the insurrection was only supported by a minority of the population, and was even opposed by many of the Bolshevik leaders themselves. This is a classic misconception about the revolution: that the Bolsheviks took power with overwhelming support of the populace.

Why was the government so easy to overthrow? No one bothered to send any military opposition. In the end, anyone who could summon such a force quite simply assumed an immediate collapse of the Bolshevik government. No one initially decided to do anything about the Bolsheviks because they assumed failure was imminent.

Part III: The Bolsheviks in Power

On March 3rd, 1918, the Bolsheviks delivered on their most popular “campaign” promise: ending the war. In surrendering to Germany they lost almost all of their European territory, along with a third of their population. If they had been able to hold on for a little while longer things would have looked much different - the Germans would surrender only 9 months later. Russian losses in World War I were staggering, with military casualties reaching around 2,000,000. For reference, American and British fatalities were 1,000,000 combined.

A few days later the capital was moved from St. Petersburg (which was renamed to Petrograd, because St. Petersburg was “too German”), to Moscow. This move represented Russia’s separation from Europe, Petrograd was a European city, whereas Moscow embraced Russia’s Asiatic traditions.

The Fight for the Soul of Russia

Although leaving World War I would not bring peace to Russia. Anti-Bolshevik forces eventually realized the Bolshevik government wasn’t going to imminently implode, so they started a civil war. The opposition force was called the White Army and their goal was to oust the Bolsheviks and return Russia to the pre-revolutionary order.

The White army was hilariously top-heavy. Out of the first 3000 troops recruited, only 12 were non-officers. The Bolshevik Red Army on the other hand had the opposite problem - they had too many rank-and-file soldiers with no officers to lead them. The Whites were better trained, and pound for pound would have decisively defeated the Reds in any battle if it were not for the Red’s tremendous numerical advantage. The Red Army at times outnumbered the Whites ten to one.

It’s also worth noting that the Whites had the backing of the Allies. At first glance this looks like an early attempt by the West to combat communism, but that’s a misinterpretation of the situation. Remember that World War I was still raging and the Allies were pissed that Russia dropped out. The leaders of the White Army promised to re-join the war once the Bolsheviks were defeated, which was all the Allies needed to hear before they began supplying them with munitions. (On a side note, the great irony of the Schlieffen plan was that the opposite ended up happening - the Germans eventually got their single-front war, just not the one they were expecting.)

How were the Bolsheviks doing? It’s hard to say if they were doing well or doing poorly…but they were definitely doing. Soon after they took over, a general terror began on anyone deemed to be wealthy. “Loot the Looters” was the phrase used to justify the stealing of anything owned by the bourgeois. The movie Doctor Zhivago does a good job depicting what this was like - there is a scene where the main character comes home to dozens of people living in his flat.

Soviet officials, bearing flimsy warrants, would go round bourgeois houses confiscating typewriters, furniture, clothes and valuables 'for the revolution'. Factories were taken out of private ownership, shares and bonds were annulled, and the law of private inheritance was later abolished.

Additionally, Lenin implemented an economic system called “war communism”, which had the explicit goal of winning the civil war. This is one of the first parts of the book that Figes begins to dive into the economic system and its underlying philosophy. War communism was the prototype of Stalin’s economy - all private trade was abolished, all major industries were nationalized, the government assumed control of the labor market, and agriculture was collectivized. This was the most extreme economic experiment ever run. Even socialists outside of Russia were not sure what was happening:

Foreign socialists were shocked by the violence of the Bolsheviks' hatred of free trade. The Bolsheviks did not just want to regulate the market - as did the socialists and most of the wartime governments of Europe - they wanted to abolish it. 'The more market the less socialism, the more socialism the less market' that was their credo.

Ok, what’s going on here? The ungenerous interpretation is that the Bolsheviks were all extremists and this was Lenin’s goal from the start. The more generous read is that this was a war-time necessity to ensure the army had the supplies it needed, like a Defense Production Act on steroids. However, Figes explains that the key motivation behind war communism was to wage war against the enemies of the Bolsheviks. Remember that the previous owners of industry were all likely actively assisting the Whites, this was the best way to neutralize them.

Aside from war communism, the Bolsheviks used another tactic in the war against the Whites, which became known as the Red Terror. However, the Red Terror was preceded by two events that we need to briefly dive into.

First, we return for a final time to Nicholas, who had been on house arrest for the last year. The Bolsheviks debated putting him on trial, which Trotsky would have won decisively, but they eventually decided against it. Learning from the French Revolution, putting the tsar on trial presumed a priori that he could be innocent, “leaving the moral legitimacy of the revolution open to question”. On July 17th, 1918, Nicholas and his entire family were shot in the basement of the house they had been confined to. The only member of the family to survive was their spaniel, Joy.

The second event that directly kicked off the Red Terror was an assassination attempt on Lenin on August 30th, which left him severely wounded. In order to understand the magnitude of this, we have to remember that Lenin was a quasi-deity to the Bolsheviks. Lenin's close call with death made the Bolsheviks realize there were too many enemies within their midst, so they decided to kill all of them.

Habeas corpus who? Anything labeled as “counter-revolutionary behavior” could put you behind bars, exiled, or shot; and any burden of proof was non-existent, it was guilty before proven innocent. Lenin had said that it was better to arrest a hundred innocent people than run the risk of even one enemy going free. The enforcers of the Red Terror were the Cheka, the secret police force that would turn into the KGB a few decades later. The atrocities of these guys feels like it's out of the middle ages, remember this was only 100 years ago:

The ingenuity of the Cheka's torture methods was matched only by the Spanish Inquisition. Each local Cheka had its own speciality. In Kharkor they went in for the glove trick' - burning the victim's hands in boiling water until the blistered skin could be peeled off, this left the victims with raw and bleeding hands and their torturers with human gloves'. The Tsaritsyn Cheka sawed its victims' bones in half. In Voronezh they rolled their naked victims in nail-studded barrels. In Armavir they crushed their skulls by tightening a leather strap with an iron bolt around their head. In Kiev they affixed a cage with rats to the victim's torso and heated it so that the enraged rats ate their way through the victim's guts in an effort to escape. In Odessa they chained their victims to planks and pushed them slowly into a furnace or a tank of boiling water. A favourite winter torture was to pour water on the naked victims until they became living ice statues. Many Chekas preferred psychological forms of torture. One had the victims led off to what they thought was their execution, only to find that a blank was fired at them. Another had the victims buried alive, or kept in a coffin with a corpse. Some Chekas forced their victims to watch their loved ones being tortured, raped or killed.

An estimated 100,000 people were executed in the Red Terror.

Just so you don’t go thinking there are any good guys in this story, the White Army was also committing atrocities against a group that they felt was their biggest enemy: the Jews. Antisemitism had always been pretty bad in Russia, but it spiked to even higher levels by the counter-revolutionaries since most of the Bolshevik leaders outside of Lenin were Jewish. The accusations followed the traditional anti-semetic playbook, that the Jews were pulling the strings controlling everything. Figes writes:

Many pogroms were accompanied by gruesome acts of torture on a par with those of the Red Terror. In the town of Fastor the Cossacks hung their victims from the ceiling, releasing them just before they choked to death: if their relatives, who watched this in terror, could not pay up the money they had demanded, the Cossacks repeated the operation. The Cossacks cut off limbs and noses with their sabres and ripped out babies from their mothers' wombs. They set light to Jewish houses and forced those who tried to escape to turn back into the fire. In some places, such as Chernobyl, the Jews were herded into the synagogue, which was then burned down with them inside. In others, such as Cherkass, they gang-raped hundreds of pre-teen girls. Many of their victims were later found with knife and sabre wounds to their small vaginas. One of the most horrific pogroms took place in the small Podole town of Krivoe Ozero during the final stages of the Whites' retreat in late December. By this stage the White troops had ceased to care about world opinion and, as they contemplated defeat, threw all caution to the winds.

The Whites killed more than 150,000 jews.

By April 1920, the Whites had lost the war. The size of their army was likely the primary cause, but the core issue was their inability to put politics over tactics. They didn’t realize that the fight was for the soul of the nation, not a war against an army. It was a battle of ideologies, not soldiers. The Whites failed to rally nearly any peasants to their cause, and the ones that did join, soon left in mutiny. The peasants didn’t like the Bolsheviks, but the Reds at least stood for something different, for change, which was more than the Whites could say. The Whites just promised to bring things back to the way they were, and the people wanted nothing to do with that.

The Bolsheviks in Charge

With the end of the civil war, we get to see an unencumbered view into Bolshevik Russia. For starters, they ironically developed a massive upper class. Top members of the party lived in compounds previously owned by the nobles of the monarchy. In a similar vein, the bureaucracy ballooned to epic proportions, under a complete command economy, the number of “officials” exploded. By 1920 there were 16 factory officials for every 100 factory workers, and in the most extreme example, 71% of the workers at the Putilov metal plant were petty officials and clerks. “All the strikes of these years complained about factory officials living off the backs of the workers.”

A few months after the war, Lenin replaced the straightforwardly named war communism with the equally straightforwardly named New Economic Policy (NEP). The NEP was an adjustment to war communism that allowed individuals to own small and medium sized businesses, although the state continued to maintain control of large industries.

Lenin also looked to science as the way to control human behavior to turn people into “cogs of the state”. Perhaps apocryphally, Lenin goes to the house of Ivan Pavlov, of salivating dog fame, to see if it would be possible to remove the individualistic tendencies of the Russian people. While any work with Pavlov failed to materialize (or most likely never occurred), a party leader named Aleksei Gastev developed many theories in line with the cogs of the state approach:

Gastev's aim, by his own admission, was to turn the worker into a sort of 'human robot' (a word, not coincidentally, derived from the Russian verb to work, rabotat). Since Gastev saw machines as superior to human beings, he thought this would represent an improvement in humanity. Indeed he saw it as the next logical step in human evolution. Gastev envisaged a brave new world where 'people' would be replaced by proletarian units' so devoid of personality that there would not even be a need to give them names. They would be classified instead by ciphers such as 'A, B, C, or 325, 075, 0, and so on'. These automatons would be like machines, 'incapable of individual thought', and would simply obey their controllers. A 'mechanized collectivism' would 'take the place of the individual personality in the psychology of the proletariat'. There would no longer be a need for emotions, and the human soul would no longer be measured 'by a shout or a smile but by a pressure gauge or a speedometer.

A few comments on this. First, it's really easy to see where Rand and Orwell’s inspiration came from. But it’s not clear to me how much of this was just the idealistic vision of some leaders, or something that was actually attempted. On one hand, inspired by what Ford had done in America, they are just trying to perfect factory efficiency, which is something I can get behind. I don’t really have an issue of turning a worker into a robot, at work. Although the latter half of the paragraph makes me want to get my Guy Fawkes mask and spray paint “who is John Galt?” onto the nearest government building.

Despite moderate success with getting support from workers who lived in the cities, the Bolsheviks failed to get any support from the peasants. They looked at the villages of poor farmers as backwards, representing the type of place that Russia wanted to get away from. They were never able to split the peasantry along class lines. The egalitarian nature of the peasant communities led them not to see themselves as poor and their neighbors as rich, they just saw each other as fellow villagers. They became highly skeptical of the intelligentsia from the city telling them they should despise their neighbor.

Part of the Bolshevik tactic to break the peasants was to attack the only other institution vying for power in Russia during the 1920s: religion. Atheism being a core tenet of communism, they attempted to replace G-O-D with G-O-V. Things then got a little weird…

In private life, as in public, religious rituals were Bolshevized. Instead of baptisms children were ‘Octobered’.

There was also an atheist art - one especially blasphemous poster showed the Virgin Mary with a pregnant belly longing for a Soviet abortion and an equally iconoclastic theatre and cinema of the Godless.

…and indeed for adults who also changed their names - were drawn from the annals of the revolution: Marx; Engelina; Rosa (after Rosa Luxemburg); Vladlen, Ninel, Ilichand Ilina (acronyms, nicknames or anagrams for Lenin); Marlen (for Marx and Lenin); Melor (for Marx, Engels, Lenin and October Revolution); Pravda; Barrikada; Fevral (February); Oktiabrina (October); Revoliutsia (Revolution); Parizhkommuna (Paris Commune); Molot (hammer); Serpina (sickle); Dazmir (Long Live the World Revolution); Diktatura (Dictatorship); and Terrora (Terror).

Yes. There was someone in Russia in the 1920s whose legitimate name was Dictatorship.

1921 poster contrasting the march of the three kings to Bethlehem (top), with the march of the workers towards communism (below).

It is worth noting that the Bolsheviks were exceptionally progressive when it came to social issues normally tied to religion. They were the first government to legalize abortion and make it available upon request, and decriminalized homosexuality.

The cultural war against religion eventually turned hot, when the Bolsheviks began shutting down churches and shooting priests. In the end, the effort was completely unsuccessful, and if anything it rallied people closer to their religion. (This feels especially obvious in hindsight).

Due to some bad weather in late 1920 and early 1921, the Russian countryside faced one of the worst famines in history. The Russian Famine of 1921 was exacerbated by the rules the Bolsheviks had employed to win the civil war. Since they took all the peasant’s stockpiles to feed the soldiers, there was nothing left to tide them over after a particularly bad winter. In the end 5,000,000 people starved. The US actually sent temporary humanitarian aid, which the Bolsheviks begrudgingly accepted.

Lenin's health declined quickly towards the end of 1921. He had a series of strokes over the last few years of his life, each one leaving him more and more debilitated. Most of Lenin’s effort during this time is on the question of succession. In a series of letters titled Lenin’s Testament, he heaped criticism on the current leaders, specifically Trotsky and Stalin. However, the letters failed to prevent Stalin from exiling Trotsky and taking full control of the USSR.

After a final stroke, Lenin died in January 1924 at the age of 53. Stalin made sure that his body was embalmed and put under a massive monument in Moscow. In the same way as having Alexander the Great's body gave credibility to Ptolemy, the soul of the country was still with Lenin, whose power only grew with death.

Conclusion

Overall, I really enjoyed this book. Figes wrote it in a compelling way that kept my attention throughout. He analyzed the “why” of situations and didn’t just focus on the “what”, which is important in an 850-page history book.

Which gets us to the length. There were times when it felt way too long, and times when it felt way too short. It’s probably the right length for the breadth it captures, but there are parts of the story that I am interested in diving deeper into, specifically Lenin and Leninism. It’s also worth noting that Figes is a Brit writing in 1996 about Communist Russia, so his slant towards capitalism and the West is a given. I thought he mostly represented issues fairly, but I don’t know if I would even recognize what that looks like. The metaphor is a lifelong atheist listening to another lifelong atheist attempting to steelman the views of a devout religious person. It might be a good steelman, but how do I really know? I wonder what looks different if a socialist writes this book; but it seems hard to argue that the revolution and Bolshevism wasn’t a huge mess.

Although to give credit where it's due, many times throughout the story Figes would present two theories on why someone did something (usually left vs. right), proceed to explain why they are both wrong and then present a third theory that seemed to be correct. Overall, I highly recommend this book for anyone interested in the Russian Revolution.

So, what are the big lessons of the revolution?

I don’t consider myself a socialist or a communist, but I’ll stick up for them here: what we saw in Russia in the 1920s was not socialism or communism, it was Leninism. Lenin’s version of communism strayed far from the original ideals of Marx and socialism. So “we tried communism and it failed” feels a little strawman-y to me: no sane person is suggesting 1920s Leninism gets tried again.

As an aspiring revisionist I wonder what would have happened if the Mensheviks had been the ones to take power instead of the Bolsheviks. It’s not very often that we get to try different methods of human coordination on scales like this, and their nuanced take may have been more successful.

Another lesson would be to look at what excessive inequality can do to a society. Inequality is just a number until the people go hungry and tear the upper-class out of their homes. This revolution was started how revolutions usually start, not by over-regulation or excessive pronouns, but by inequality, atrocities, and hunger.

This story also shows how badly a group of intellectuals armed with theories can screw things up. Most of the Bolshevik leadership were from high class families, heavily educated, but had never stepped foot into a factory. They fought for what was best for the workers & peasants but didn’t happen to involve any in the process.

We also see what happens when society becomes too progressive too quickly. I like the metaphor of tug of war with conservatism on one end and progressivism on another. Society works best when we are slowly inching our way along. But when one side slips, we get pulled too far to the other side, and chaos ensues. The Russian Revolution gives us a clear picture into how ugly things can get when the rule of law breaks down. The number of “unnatural” casualties in Russia in the early 20th century were greater than 15 million people across war, famine, and genocide.

However, perhaps the biggest takeaway is how powerful an idea can be, especially when society is ready for that idea and there exists great characters capable of capitalizing on it. To again emphasize this last point, I will leave you with a quote from Aldous Huxley, the author of Brave New World.

“It is possible to argue that the really influential book is not that which converts ten millions of casual readers, but rather that which converts the very few who, at any given moment, succeed in seizing power. Marx and Sorel have been influential in the modern world, not so much because they were best-sellers, but because among their few readers were two men, called respectively Lenin and Mussolini.”